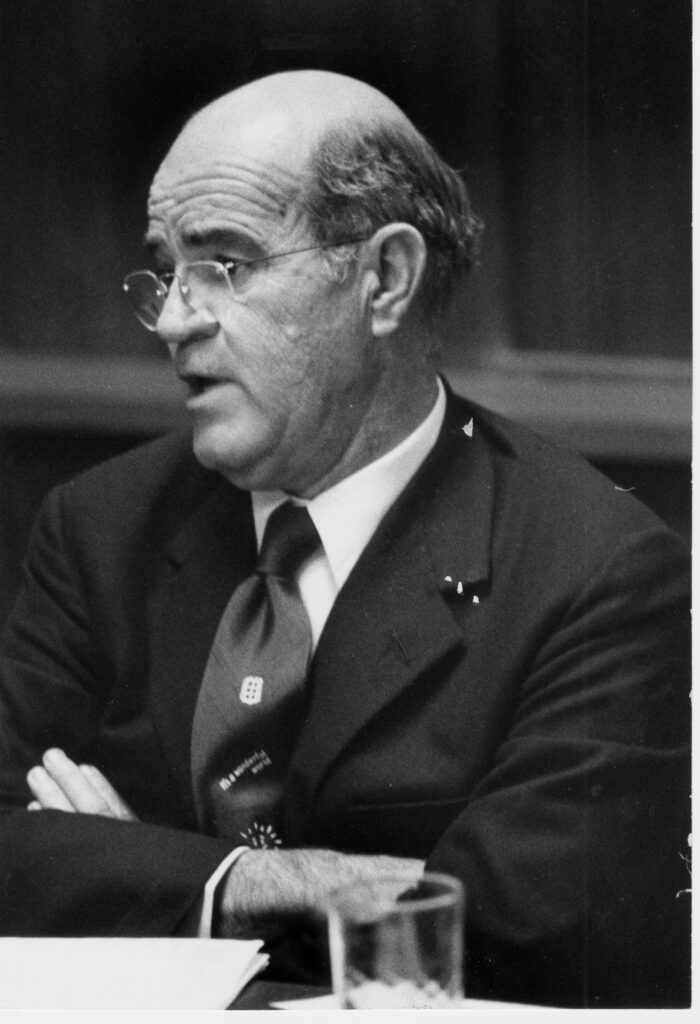

In the 1950s and 1960s Mills B. Lane Jr. played an important role in Atlanta’s political development and economic expansion. As president of Atlanta-based Citizens and Southern National Bank (C&S), Lane pioneered innovative lending practices and earned national prominence for the bank, while financing much of the city’s physical redevelopment. It was in Atlanta’s political arena, however, that his impact was perhaps most keenly felt. Working behind the scenes as a political insider, Lane leveraged his influence to promote good government and progressive candidates, and helped to build an institutional framework capable of resolving municipal disputes.

“My Father Owned the Joint”

Mills Bee Lane Jr. was born in Savannah on January 29, 1912, to Mary Comer and Mills B. Lane Sr. After graduating from Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1934, he accepted a position in Valdosta as a clerk with C&S bank, which was founded by his father in 1906. Lane married Anne Waring, and the couple had two children, Mills B. Lane IV and Anita. (Mills B. Lane III was Lane’s nephew, his brother’s son.) Lane IV would go on to found the Beehive Press in Savannah.

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The young Lane earned high marks for his fresh approach to the family business and quickly scaled the bank’s corporate ladder. Following his father’s death, Lane became bank president in 1946, a position he held for almost thirty years. When once asked to explain his success at the bank, Lane replied with equal parts humor and candor: “My father owned the joint.”

Though his lineage may have placed him on the path to the president’s office, it was Lane’s innovation and vision that allowed him to succeed once there. While president at C&S, Lane helped pioneer data processing, credit cards, “instant money,” and travel agency services to the bank’s customers. He lent money liberally, and he allowed all bank officers, even assistant cashiers, to make loans up to the bank’s legal limit. When coupled with a favorable investment climate during Georgia’s post–World War II (1941-45) economic boom, Lane’s willingness to take risks paid large dividends for the bank. By the time of his retirement in 1973, C&S had become the largest bank in the South and the most profitable among the nation’s fifty largest banks.

It was style as much as substance, however, that distinguished Lane’s leadership at C&S. Ever the showman, he amused and sometimes confounded observers with attention-grabbing stunts that might have seemed more appropriate at a carnival than at a bank. In order to promote Georgia’s wool industry, for example, Lane once herded a flock of sheep into the bank’s main lobby. To promote teamwork, he arrived at official bank meetings wearing baseball and football uniforms. And to encourage his executives to pursue bigger targets, Lane once donned a shooting jacket, stormed a C&S conference room, and unloaded a round of blank .30-caliber cartridges. “I’m a banking fugue,” he admitted, “a variation on a theme.”

Politics

Few people understood the relationship that existed between Atlanta’s economy and politics as well as Lane. As an influential member of the city’s tight-knit business community, Lane was a consummate insider, working behind the scenes to negotiate compromise and harmonize the city’s disparate voices during the civil rights movement.

After teaming with Ivan Allen Jr. to broker a desegregation compromise between members of the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce and student demonstrators in 1960, Lane managed Allen’s successful campaign for mayor the following year, and did so again in 1965. Also in 1960, at Allen’s request, Lane established the Commerce Club, an exclusive gathering place in downtown Atlanta designed to foster ties between the city’s business and civic communities. Throughout Allen’s tenure in office, Lane was a constant, if unseen, presence, advising the mayor on key decisions and underwriting much of the city’s physical development.

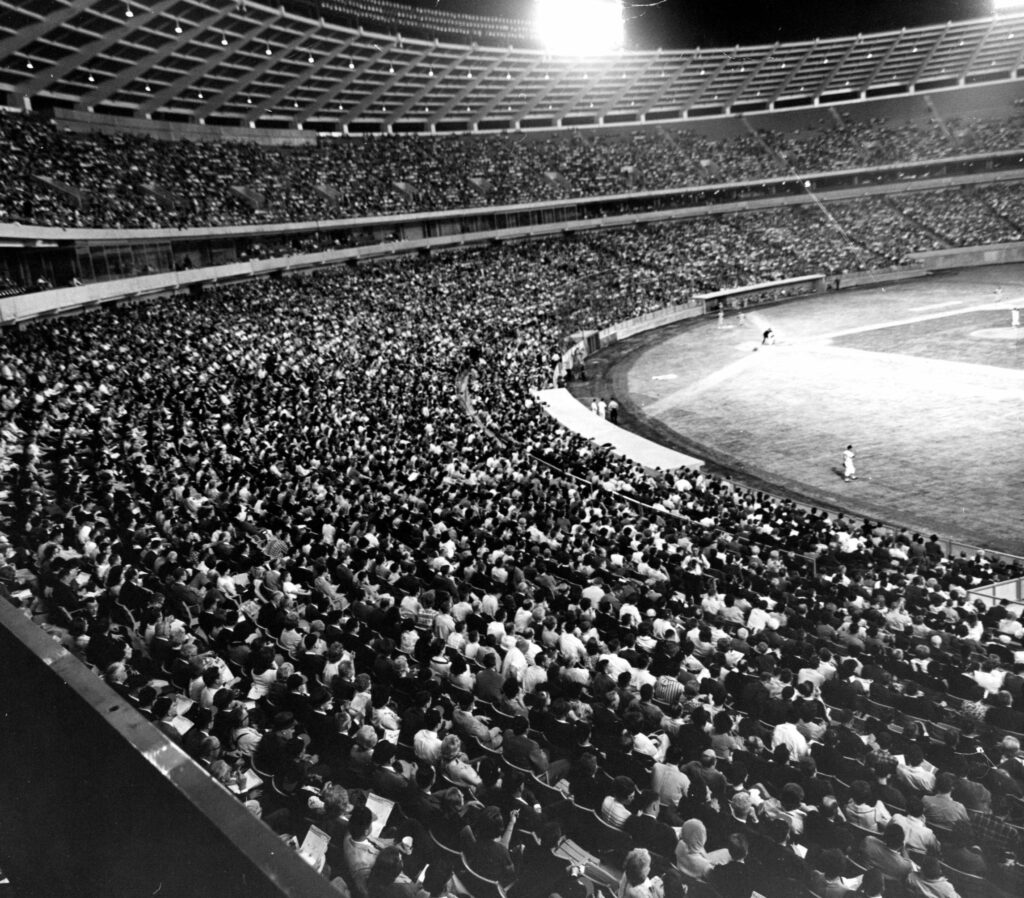

During his first term as mayor, Allen sought to lure major league baseball to Atlanta. A handful of owners expressed interest in relocating their teams to the city, but without a suitable stadium, negotiations reached an impasse. With few other options, Allen turned to his old friend Lane, who extended the city a full line of credit to finance construction of a stadium. In April 1965 the Atlanta Stadium (later Atlanta

Courtesy of Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

While his role in bringing professional sports to Atlanta may have ensured his legacy, Lane’s most enduring contribution to the city was yet to come. In 1971, when the city’s politics were undergoing a period of racial transition, W. L. Calloway, a prominent Black realtor, approached Lane to ask for the banker’s help in forming a biracial organization that would enable Atlanta to maintain amicable race relations during the difficult years ahead. Lane pledged his support before Calloway could even finish his proposal.

Action Forum, as the organization came to be known, made an immediate impact on the city’s politics. Within months of the forum’s creation, the group’s members settled a financing dispute threatening the city’s rail transit plans. Thereafter, the group continued to meet monthly and played an important, albeit informal, role in the city’s politics by defusing racial tensions, opening lines of communication, and providing an extragovernmental framework for resolving municipal disputes.

Lane’s political influence was not confined to Atlanta. When racial unrest threatened to overwhelm Lane’s native Savannah in 1963, he formed a “Committee of 100” to promote a peaceful desegregation process and secure the release of activist Hosea Williams from prison. In 1962 he supported Carl Sanders’s gubernatorial bid, helping the thirty-seven-year-old state senator from Augusta defeat former governor and segregationist Marvin Griffin. Years later, Sanders referred to Lane as “one of the great unsung heroes of our time,” and credited much of his own success to the banker’s influence. “I personally feel like my election as governor and many of the programs I initiated,” Sanders admitted, “were because of the inspiration I received from the advice and counsel of Mills B. Lane.”

Retirement

During his heyday at C&S, Lane enjoyed a reputation throughout Atlanta for boundless optimism and a relentlessly positive approach to banking and boosterism. As if to prove that good humor was in fact contagious, Lane even required junior officers at the bank to wear ties bearing his trademark expression, “It’s a wonderful world.” However, a series of personal crises toward the end of his life undermined Lane’s pleasant disposition, leaving the banker despondent and bitter in old age.

Lane left C&S in 1973 after suffering two heart attacks and diminishing eyesight. Economic conditions in the city worsened thereafter, and the bank underwent a period of severe financial distress. Richard Kattel, Lane’s handpicked successor, was ousted by federal regulators in 1977, but many observers linked the bank’s travails to decisions made during Lane’s tenure.

Upon retirement, Lane returned to Savannah, where he devoted his time and wealth to a handful of philanthropic concerns, including Savannah’s historic district, Armstrong State University, and the Georgia Council on Economic Education, which he helped found in 1972. Lane died on May 7, 1989.