In 1892 Georgia politics was shaken by the arrival of the Populist Party. Led by the brilliant orator Thomas E. Watson this new party mainly appealed to white farmers, many of whom had been impoverished by debt and low cotton prices in the 1880s and 1890s. Populism, which directly challenged the dominance of the Democratic Party, threatened to split the white vote in Georgia. Consequently, the Populists boldly tried to win Black Republicans to their cause. Such appeals outraged Democrats and visited upon the state some of the most dramatic and bloody elections in its history.

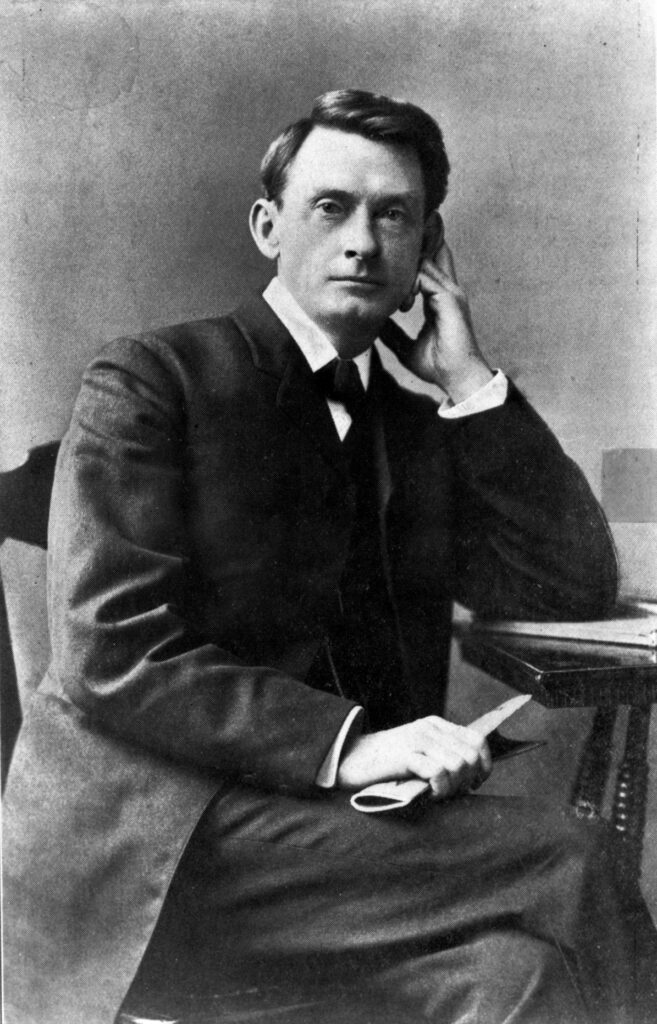

Courtesy of Georgia Historical Society.

Populism blazed across the Georgia scene only briefly. By the end of 1896, it was nearly exhausted. For better or worse, however, the movement’s short existence profoundly affected state politics. And Thomas Watson remained a commanding force in Georgia politics for more than twenty years.

Origins of Georgia Populism

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, the price of cotton steadily fell in the American South. Exorbitant railroad freight rates added to the misery of farmers. Many, both white and Black, desperately sought relief. In the late 1880s an agricultural society called the Farmers’ Alliance swept across the South, enrolling more than 100,000 members. Arguing that the American political and economic systems were rigged to serve the interests of the rich, the Alliance demanded that the government expand the money supply by printing more money and coining more silver. Such action would cause inflation (a general increase in the cost of goods and services) and drive up cotton prices.

The Farmers’ Alliance also called for banking reform, government ownership of the railroads, and the direct election of U.S. senators. (Until 1913 U.S. senators were elected by state legislatures instead of directly by citizens.) Finally, it argued for the sub-treasury plan, a scheme by which farmers at harvest could borrow money against the value of crops stored in government warehouses while waiting for prices to improve. The enemies of the Alliance denounced such proposals, claiming they would encourage governmental paternalism and undermine free enterprise. When neither the Democrats nor the Republicans would adopt the Alliance demands, the more reform-minded members of the Alliance founded the People’s Party—or, as it was more commonly called, the Populist Party.

Populism attracted followers in all of the southern states, but it was especially strong in Georgia, where it tended to flourish in regions that possessed little love for the Democratic Party. It was most successful in the old plantation country west of Augusta. Here, before the Civil War (1861-65), the Whig Party had held sway. Even after the decline of the Whigs, the region only reluctantly embraced the Democratic Party.

Populist Campaigns

In 1892 the Populist Party ran James B. Weaver of Iowa as its first presidential candidate. In Georgia the party nominated William L. Peek of Rockdale County for governor. By far, however, the party’s most exciting candidate was Tom Watson of McDuffie County. Watson, who was one of the state’s most promising young politicians, had been elected to Congress in 1890 as a Southern Alliance Democrat. Within a year he shocked Georgians by quitting his party, joining the Populists, and founding a newspaper called the People’s Party Paper. His campaign to win reelection to Congress eventually drew national attention.

Realizing that the white vote would probably split between the Populist and Democratic parties, the Populists—and Tom Watson in particular—tried to gain the support of African Americans. Although never calling for social equality, they invited two Black delegates to their state convention in 1892 and appointed a Black man to the state campaign committee in 1894. They also demanded an end to the convict lease system, a program by which the state leased its prisoners to private mining companies. Work in the mines was dangerous, conditions were brutal, and most of the prisoners were Black. Democrats quickly accused the Populists of allying with formerly enslaved people. Such racist claims drove many whites from the People’s Party movement, and the contest was marked by fistfights, shootings, and several murders. On election day, William J. Northen, the Democratic candidate for governor, easily triumphed over Peek, though blatant corruption at the polls was needed for Northen to defeat the Populist Watson.

Within a year, the United States was shaken by the Panic of 1893, one of the worst depressions in its history. Railroads, banks, and businesses collapsed, and millions of people lost their jobs. The average price of cotton fell to a ruinous price, less than five cents a pound. The Democrats failed to do anything of substance to fight the Panic. This, in turn, offered Populists a promising opportunity during the Georgia elections of 1894. Hoping to appeal to urban middle-class voters while holding onto its supporters in the countryside, the People’s Party nominated James K. Hines of Atlanta for governor. An urbane lawyer from a distinguished family, Hines was also noted for his support of reform. The voting in the gubernatorial race was so close that election officials needed several days to determine who had won. (Populists believed that the extra days were needed to doctor the ballots.) In the end, William Y. Atkinson, the Democratic candidate for governor, was declared the victor, having taken 55.6 percent of the vote.

In 1894 Watson again ran for Congress. As in 1892 the campaign was bitterly contested and Watson was once more defeated. This time, however, the results were so suspicious (many counties had produced more votes than voters) that Watson’s opponent agreed to a new election. But when this contest was held a year later, Watson again lost. As in 1892 and 1894, Populists believed Watson had been robbed of victory.

Despite such defeats, Populists eagerly awaited the presidential election of 1896. They firmly believed the Republicans and Democrats would nominate conservatives for president and thus split the ranks of their enemies. In this, they were only half right. The Republicans did as expected and nominated a conservative, William McKinley of Ohio. But the Democratic convention was taken over by its silver wing, which called for moderate inflation by means of the coinage of silver. After delivering his famous “Cross of Gold” speech, William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska received the Democratic nomination for president.

Populists across the country were stunned by the results of the Democratic convention. Bryan had adopted only one of the third party’s many demands. Even so, if the Populists nominated a candidate, it would divide the reform vote and ensure the election of McKinley. On the other hand, if they failed to nominate a candidate, many feared their party would collapse. In the end, delegates at the Populist national convention agreed upon an awkward compromise. They nominated Bryan for president and, to preserve their party identity, they nominated Tom Watson for vice president.

While Watson campaigned in many parts of the country, Georgia Populists ran Seaborn Wright, a prominent Prohibitionist from Floyd County, for governor. The third-party attempt to fuse with the Democrats on the national level, and with the Prohibitionists on the state level, failed badly. McKinley defeated Bryan, and William Y. Atkinson, the Democratic candidate for governor of Georgia, took nearly 60 percent of the vote. Watson soon retired from politics. For all practical purposes, the Populist Party was dead.

Populist Demise

After the defeat of 1896, white Populists slowly drifted back to the Democratic Party. But few forgot their political heritage. In 1906 Tom Watson came out of retirement to support the gubernatorial campaign of Hoke Smith, a Progressive from Atlanta. Watson also demanded the disenfranchisement of Black voters. This about-face, and a growing eccentricity in Watson’s behavior, troubled some former Populists. Nevertheless, thanks to Watson’s support and the support of most of the former Populist counties, Hoke Smith was elected. Smith led the fight for many of the reforms that Populists had once demanded, including prohibition and an end to convict leasing, but he also oversaw a successful campaign to disenfranchise the African American voter in Georgia.

Populism and Race

The relationship of Populism to race is one of the most perplexing features of the third-party movement, especially in light of Watson’s betrayal of Black voters in the early twentieth century. In the 1890s the third party desperately needed the Black vote and made concessions to gain it. Yet as each year passed, fewer and fewer Blacks supported the movement. What kept Black Georgians from supporting Populism with more fervor?

There are many answers to this question. But Blacks ultimately came to believe that the movement offered them little and that Populist appeals had more to do with opportunism than friendship. In fact, the Populists often appeared as prejudiced as Democrats, if not more so. In some places, such as Watson’s congressional district, the third party even employed the Ku Klux Klan to intimidate Blacks who wanted to vote Democratic. Although some African Americans remained loyal to Populism, most quickly grew disillusioned and returned to the Republican Party.