Sapelo Island, situated about sixty miles south of Savannah, lies in the center of coastal Georgia’s well-defined chain of barrier islands. The 16,500-acre island is Georgia’s fourth largest and, excepting the 434-acre African American community of Hog Hammock, is entirely state owned and managed.

The island comprises various entities in addition to Hog Hammock, including the University of Georgia Marine Institute, the Richard J. Reynolds Wildlife Management Area, and the Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research Reserve. The latter two are administered by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Early History

The human history of Sapelo dates back at least 4,500 years. Archaeological investigations on the island have determined an extensive Native American presence on Sapelo during the Archaic Period of prehistory (2,000-500 B.C.). The name Sapelo is of Indian origin, being adapted to Zapala by Spanish missionaries, who established themselves on the island from about 1573 to 1686. The Franciscan mission of San Josef was situated on the north end of the island at or near the Native American Shell Ring, a prehistoric ceremonial mound that represents one of the most unusual archaeological features on the Georgia coast.

Colonial Period

English colonization of Georgia beginning in 1733 led to an agreement with the Creek Indians by which the colony acquired the land between the Savannah River and the Altamaha River, with the Indians reserving hunting lands on several barrier islands, including Sapelo. In 1757 another treaty with the Creeks resulted in the cession of Sapelo, Ossabaw, and St. Catherines islands to the royal colony.

Early private owners of Sapelo included Patrick Mackay, who grew crops there before the Revolutionary War (1775-83), and John McQueen. In 1789 a consortium of Frenchmen who planned to develop the island for agricultural, live-oak timbering, and livestock operations acquired Sapelo. The French involvement on Sapelo was characterized by mystery, intrigue, and mayhem. Disagreements over the use of the island and mistrust over expenditures of funds led to the breakup of the six-man French partnership by 1795. One of the men, Chappedelaine, was shot and killed by one of his partners in a duel on the island; another partner, Dumoussay, died of yellow fever a few weeks later.

Nineteenth-Century Plantation Economy

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Sapelo was acquired through purchase or inheritance by three men, all of whom left their imprint on the island. They were Thomas Spalding (south end), Edward Swarbreck (Chocolate), and John Montalet (High Point), the latter having married the daughter of one of the departed Frenchmen. By 1843 Spalding had acquired almost the entire island, except a tract of several hundred acres at Raccoon Bluff owned by the Kimberly-Street family.

Spalding left the most important legacy to Sapelo. He was one of the leading planters on the tidewater, an agricultural innovator, amateur architect, astute businessman, and leading citizen of McIntosh County. Spalding introduced the cultivation of sugar cane and the manufacture of sugar to Georgia. He built his own sugar mill, commissioned a lighthouse for the island in 1820, reintroduced the use of tabby as a primary building material on the coast, contributed important techniques for the culture of Sea Island cotton, and gradually developed Sapelo into an antebellum plantation empire. Spalding and his children owned 385 enslaved laborers on Sapelo in the 1850s.

African American Settlements

The Civil War (1861-65) ended the plantation economy, and Sapelo remained home to a large African American community during the Reconstruction and postbellum periods. The William Hillery Company, a partnership of freedmen, bought land at Raccoon Bluff as early as 1871. Over time, many of the freedpeople purchased land on Sapelo and established permanent settlements, including Hog Hammock, Raccoon Bluff, Shell Hammock, Belle Marsh, and Lumber Landing. The First African Baptist Church was organized in 1866 at Hanging Bull, eventually moving to Raccoon Bluff, which was also the site of a Black school. Sapelo’s Blacks engaged in subsistence agriculture, timbering, and oyster harvesting in the Duplin River estuary.

Twentieth Century

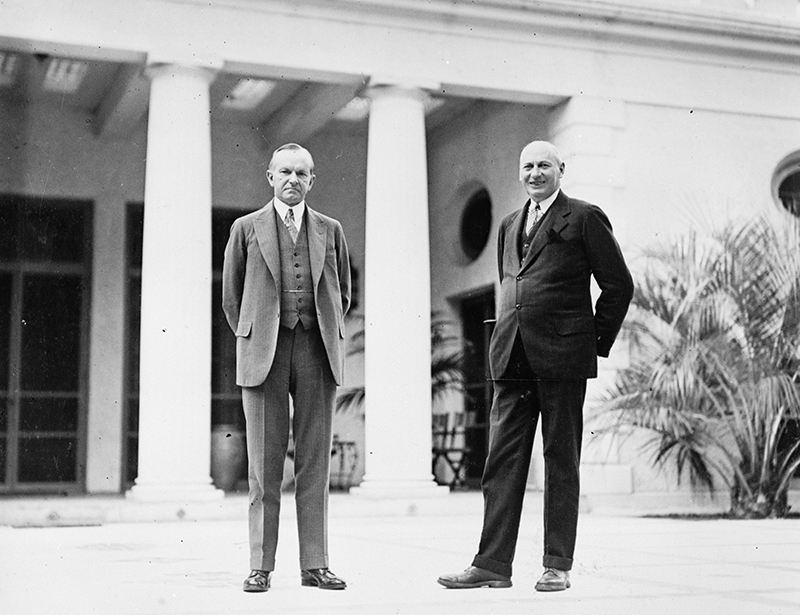

Most of Sapelo was sold by Spalding descendants after the Civil War. In 1912 Detroit, Michigan, automotive engineer Howard Coffin consolidated the various holdings on Sapelo and bought the entire island, except for the Black communities, for $150,000. Coffin owned Sapelo for twenty-two years. Between 1922 and 1925 he rebuilt the south-end mansion—a tabby-stucco structure originally built by Spalding in 1810—into one of the most palatial homes on the coast. Coffin engaged in large-scale agriculture, sawmilling, and seafood harvesting. He also built roads, drilled artesian wells, and added other improvements to the island. Many distinguished visitors were guests of the Coffins on Sapelo, including U.S. presidents Calvin Coolidge (1928) and Herbert Hoover (1932), and aviator Charles A. Lindbergh (1929). During this period Coffin and his young cousin Alfred W. Jones established the Cloister resort on nearby Sea Island.

In 1934, due to financial reversals brought on by the depression, Coffin sold Sapelo to North Carolina tobacco heir Richard J. Reynolds Jr. Reynolds utilized the island as a part-time residence for thirty years. During this time, he consolidated the Black holdings on the island into one community at Hog Hammock. Reynolds’s most important contribution was establishing the Sapelo Island Research Foundation and providing facilities and other support for the University of Georgia Marine Institute, begun in 1954. His widow, Annemarie Schmidt Reynolds, sold Sapelo to the state of Georgia in two separate transactions in 1969 and 1976.

Approximately 115 people now reside on Sapelo, either permanently or temporarily, with the majority of them at Hog Hammock. That community still consists primarily of descendants of Thomas Spalding’s enslaved workers, and their diminishing numbers are a source of concern. Cornelia Walker Bailey, the most prominent spokesperson for the community, championed the preservation of Sapelo’s rich West African heritage, from spiritual beliefs and folkways to the Geechee dialect once spoken by the island’s African American residents. In 2000 Bailey published a “cultural memoir” of her life and the struggle to preserve these traditions, God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man.