Georgia’s secession from the Union followed nearly two decades of increasingly intense sectional conflict over the status of slavery in western territories and over the future of slavery in the United States. The secession of southern states hastened the outbreak of the Civil War (1861-65).

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Secession had been seriously mentioned as a political option at least as far back as the Missouri crisis of 1819-21, and threats to disrupt the Union occurred in every sectional crisis from the nullification era (1828-33) onward. White Georgians, along with other white southerners, disagreed over whether secession was a constitutional right (embodied in the national compact that grew out of the 1787 Constitutional Convention) or a natural right of revolution (arising from the inherent power of the people to form and abolish governments). But in a practical sense this distinction mattered less than the fact that secession was widely recognized as a legitimate remedy for southern grievances. As sectional strife over slavery intensified in the mid-nineteenth century, some southern agitators pressed for immediate secession.

The Georgia Platform, a response to the Compromise of 1850, accepted the terms of the unpopular Compromise but also satisfied secessionists by declaring that further assaults on slavery in the South or in future states would be unacceptable. The writers warned that northern contempt of the Platform would make secession inevitable. Thus, when Abraham Lincoln, the candidate of the antislavery, northern Republican Party, won the 1860 presidential election, states in the lower South moved quickly to call state conventions to consider secession. Georgia’s state legislature set January 2, 1861, as the election date for a state convention, which was to meet on January 16.

Opposing camps formed rapidly in the campaign for the election of county delegates to the state convention. Immediate secessionists, mostly former Democrats headed by Howell Cobb, Thomas R. R. Cobb, Joseph E. Brown, Henry Rootes Jackson, Robert Toombs, and others, believed that Lincoln’s election violated the spirit of the U.S. Constitution and provided clear evidence that a tyrannical northern majority intended to trample on southern rights and ultimately abolish slavery. Honor and safety depended, immediate secessionists argued, on severing ties with the Union as quickly and completely as possible, to protect the South from its enemies and promote southern unity. Immediate secessionists had the advantage of a decisive plan of action and a strong set of allies in neighboring Deep South states—South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, and Alabama would secede before Georgia’s state convention even met.

Cooperationists, a varied collection of former Whigs and conservative Democrats, were led by Alexander Stephens, Herschel Johnson, and Benjamin Hill. Cooperationists agreed that the South faced great dangers and that Republicans must provide strong guarantees to protect slavery and southern rights if Georgia were to remain in the Union. In other words, cooperationists differed from immediate secessionists more in tactics than in underlying principles. Cooperationist plans for delay and deliberation typically involved holding a convention of southern states to frame ultimatums that would extract concessions from the Republican Party. The secession of nearby states, however, made the logic of cooperationist proposals suspect and weakened their resolve; they were far less active during the campaign than their immediate secessionist counterparts.

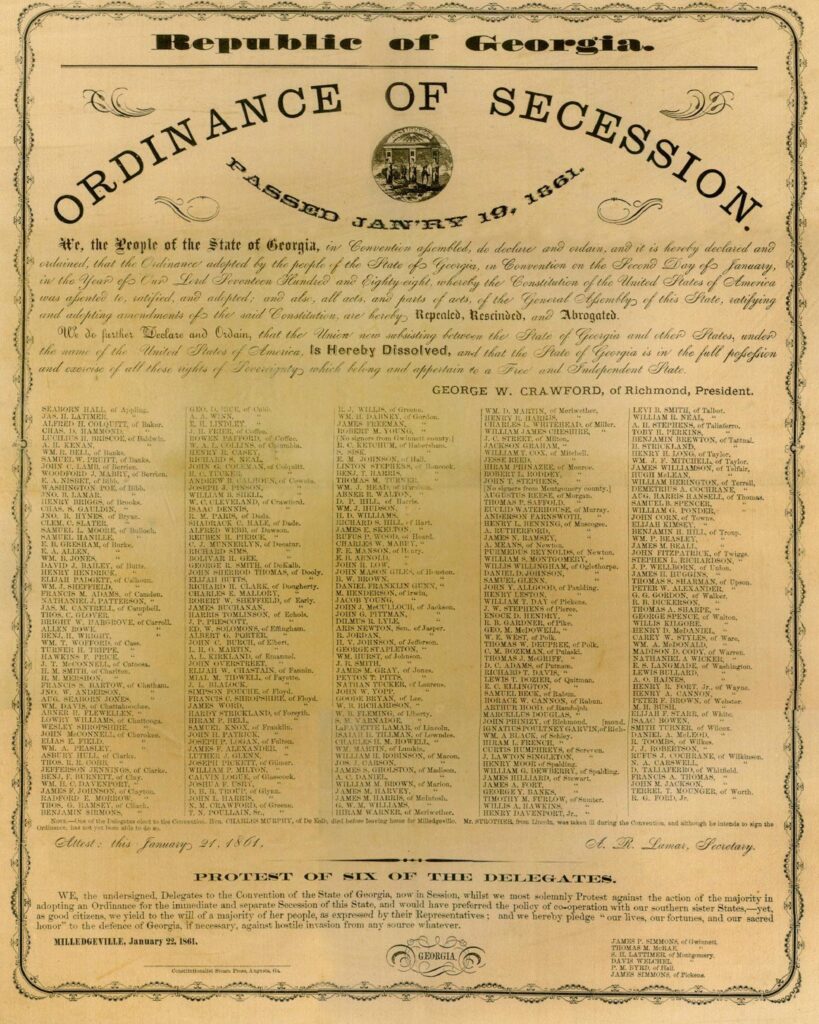

Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.

White Georgians spoke very clearly on the issues at stake in 1860-61. A series of debates was held in the state capital of Milledgeville, and county conventions denounced northern aggression; reiterated familiar claims regarding southern rights to expand slavery into the territories; vigorously defended southern honor; conjured up the horrors of abolitionism, race war, and racial amalgamation; and insisted upon security for the South’s peculiar institution. Liberty and freedom, for the white male voters of Georgia, meant preserving their right to enslave people and to rule their family households without interference from outside forces, most especially from the federal government, which in their view had fallen into the hands of abolitionist fanatics. Republican and northern hostility to slavery was cited as the sole compelling reason for contemplating secession, and white Georgians agreed that what they interpreted as repeated and unprovoked assaults upon slavery must cease or the Union must be dissolved.

The exact results of the January 2 election, in terms of total votes cast for each side statewide, will probably never be known: there were voting irregularities, and some of the candidates held ambiguous positions. Although the unofficial count released—not until April—by Governor Joseph E. Brown showed a lopsided victory for the immediate secessionists, the best evidence indicates that they won, at best, a tiny majority of the ballots cast, 44,152 to 41,632. Outside of the mountain counties (strongly cooperationist) and the coastal counties (overwhelmingly for immediate secession), voting patterns were mixed. Black Belt counties—those characterized by large plantations and large enslaved populations—that had supported the Whig Party in the 1830s and 1840s and had voted against southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge in the 1860 presidential election tended toward cooperationism, while Democratic counties in the Black Belt that had supported Breckinridge generally favored immediate secession. Although only about 40 percent of white families in Georgia enslaved African Americans (a considerably higher percentage than in the South as a whole), no clear-cut divisions along slaveholder/nonslaveholder lines appeared at the polls.

The Georgia state convention opened on January 16, 1861. It was an impressive assemblage, including Alexander Stephens, Robert Toombs, Eugenius A. Nisbet, Herschel Johnson, and Benjamin Hill; former governor George W. Crawford presided. Despite the closeness of the election, immediate secessionists had a controlling majority. The crucial vote occurred on January 18, when Nisbet offered resolutions for immediate secession and Johnson countered with a proposal for a convention of the southern states. Johnson’s plan embodied the cooperationist formula of seeking redress for grievances in the Union, while reserving secession as the ultimate remedy. Georgia’s conditions for remaining in the Union, as outlined by Johnson, included constitutional amendments opening all territories to slavery and providing for the unrestricted admission of new slave states, along with the repeal of personal liberty laws (laws that impaired the ability of slave owners to recover fugitives from slavery) in the northern states. After debate, the convention passed Nisbet’s resolutions by a 166-130 vote. The next day, January 19, the delegates voted 208-89 to adopt an ordinance of secession. On January 21 the ordinance of secession was publicly signed in a lengthy ceremony.

Georgians participated actively in the subsequent congress in Montgomery, Alabama, which wrote a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America. Howell Cobb presided over the Montgomery congress, which also formed a provisional Confederate government, naming Jefferson Davis of Mississippi as president and Georgia’s Alexander Stephens as vice president.