Lillian Smith was one of the first prominent white southerners to denounce racial segregation openly and to work actively against the entrenched and often brutally enforced world of Jim Crow. From as early as the 1930s, she argued that Jim Crow was evil (“Segregation is spiritual lynching,” she said) and that it leads to social and moral decay.

Literary Works

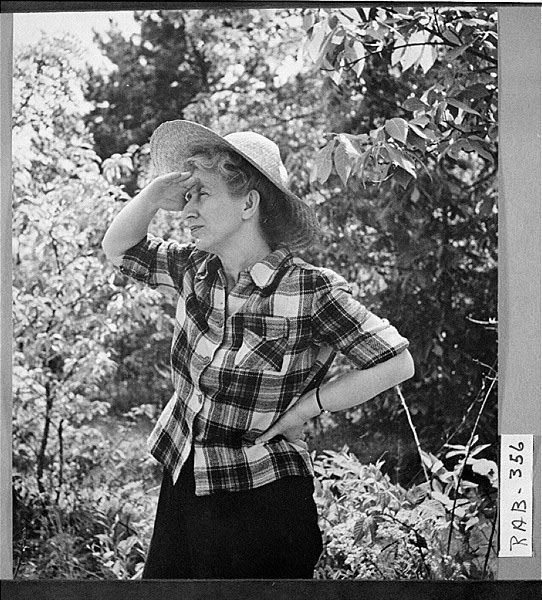

Smith gained national recognition—and regional denunciation—by writing Strange Fruit (1944), a bold novel of illicit interracial love. Five years later she hurled another thunderbolt against racism in Killers of the Dream (1949), a brilliant psychological and autobiographical work warning that segregation corrupted the soul; removed any possibility of freedom and decency in the South; and had serious implications for women and children in particular in their developing views of sex, their bodies, and their innermost selves. From her home in Clayton, atop Old Screamer Mountain, she openly convened interracial meetings, and she toured the South, talking to people from all races and classes. She was unsparing in her criticisms of “liberals” and “moderates” like Atlanta’s famed Ralph McGill and refused to join groups such as the Southern Regional Council until it could oppose segregation as well as racism. In her own psyche she struggled with intensely conflicting desires: to write creatively, following her heart’s passions, or to respond to her stern conscience and the intellectual voice of duty.

Smith’s writings, her investigative tours of the South, and the interracial conferences were signs that intellectual and social change was brewing in the South. By the time the civil rights movement made its dramatic debut in the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott in 1955, Smith had been meeting or corresponding with many Black southerners and concerned whites for years and was well informed about the conditions in which African Americans lived, and about their anger and frustration. She corresponded with civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. and publicly admired his work. She remained unflinchingly dedicated to him until her death. Smith greeted the historic 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing school segregation as “every child’s Magna Carta.” The following year she wrote Now Is the Time, a tract appealing for compliance with the high court’s decision. Her other writings were diverse—from The Journey (1954), a book of autobiographical musings and social commentary based on a driving tour of coastal Georgia that she made in 1952, to One Hour (1959), an attack on McCarthyism thinly disguised as a novel.

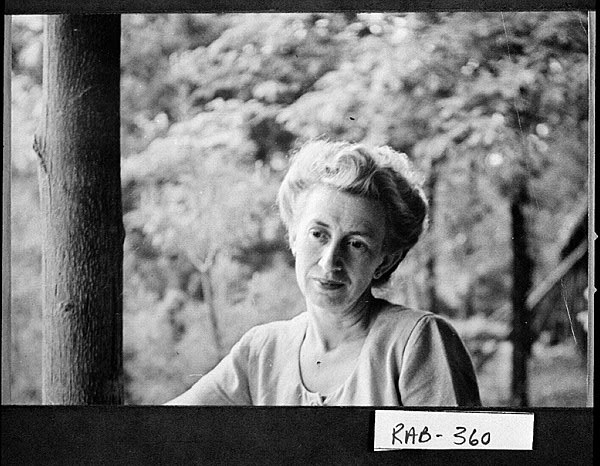

Life

Lillian Eugenia Smith was born into a large, prosperous family in Jasper, Florida, on December 12, 1897. When the family business collapsed in 1915, her family moved to their cottage in Clayton, in Rabun County, and started Laurel Falls Girls Camp. Smith studied at Piedmont College (now Piedmont University) in Demorest (1915-16) and then left to help run the family camp. Pursuing her great love of music, she also did two stints at the Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, Maryland (1917, 1919). In 1922 she went to China to offer musical instruction at a Methodist missionary school. When her parents’ health began to fail in 1925, she came home and eventually took over the running of the camp, which in time she converted into a place for serious discussion of social issues. Her longtime partner, Paula Snelling, a school counselor, assisted her.

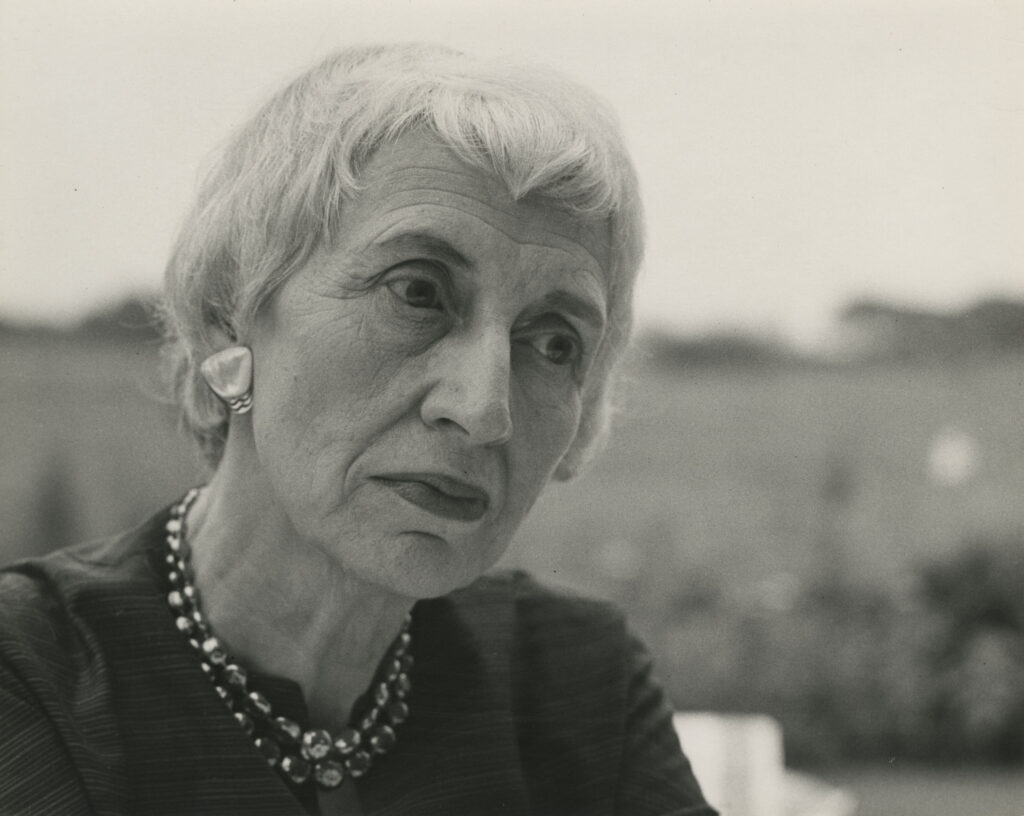

In 1936 the two founded Pseudopodia, a small magazine meant to further their ideals and to give southern writers, including Black southerners, a forum. After several renamings, including South Today, Smith closed the successful magazine in 1945 to devote herself to writing. Unfortunately, none of her books achieved the emotional power of her controversial novel Strange Fruit or the intellectual and psychological depths of Killers of the Dream. She battled cancer from the early 1950s until her death in 1966, but to the end she remained devoted to her dream of a South liberated from the “ghosts” of southern traditions. Her last published work was Our Faces, Our Words (1964), which applauded nonviolence in the civil rights movement.

It is arguable that Smith’s sojourn in China, where she witnessed prejudice, oppression, and constant violations of her youthful Christian principles, compelled her to become an outspoken social critic. But she was not a churchgoer and did not refer to herself as religious. She read the giants of intellectual modernism (namely, Freud) with great passion and cited modernist writers (Henri Bergson, Carl Jung, and Paul Tillich among others) in her attack on prejudice and narrowmindedness. Her own sexual orientation and personal life gave her a clearly existential understanding (she read most of the main existentialists of her day) of what it meant to be part of a despised minority considered deviant and dangerous by many.

Legacy

By and large, Smith’s neighbors were polite to her, but she knew what many southerners thought of her and could decipher the ugliness of the expression, uttered by Eugene Talmadge, that Strange Fruit was a “literary corncob.” Fred Hobson has written that Lillian Smith “was not afraid to confront the darkness within Southern, and American, society—racially, sexually, and politically. She was, in the finest sense of that term, a moralist, an absolutist, one of the last of the all-or-nothing voices.” Though her fame may have diminished since her death, she was an important early voice in the movement for civil rights in the American South, one of the first white southern writers to confront the evils of racism and injustice in a forthright, uncompromising manner.

Smith was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement in 1999 and into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame in 2000.