Most famous for serving as the vice president of the Confederacy during the Civil War (1861-65), Alexander Hamilton Stephens was a near-constant force in state and national politics for a half century. Born near Crawfordville, in Taliaferro County, on February 11, 1812, to Margaret Grier and Andrew Baskins Stephens, the young Stephens was orphaned at fourteen, which intensified his already melancholic disposition. He graduated from Franklin College (later the University of Georgia) in 1832 and gained admittance to the bar two years later. There followed a steady and uninterrupted rise to political prominence.

Early Career

Frail and sickly, the lifelong bachelor poured his nevertheless considerable vigor into public life. Elected as a Whig to the state legislature in 1836, he served there for seven years. During his political apprenticeship Stephens made a lifelong friend and ally in a man who was in many ways his opposite, the robust and blustery Robert Toombs. He moved on in 1843 to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he remained until 1859. Like most southern Whigs, Stephens maintained a delicate balance between supporting states’ rights and backing the party’s nationalist program. An ardent defender of slavery, he favored the annexation of Texas but also played a critical role in getting the Compromise of 1850 passed. In the early 1850s, Stephens and Toombs seized leadership of the state party from the less politically skilled John Macpherson Berrien. The team later put its weight behind the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and both men resisted secession before U.S. president Abraham Lincoln’s election. Unlike Toombs, though, Stephens continued to oppose separation right up to the time it became a certainty for Georgia in January 1861.

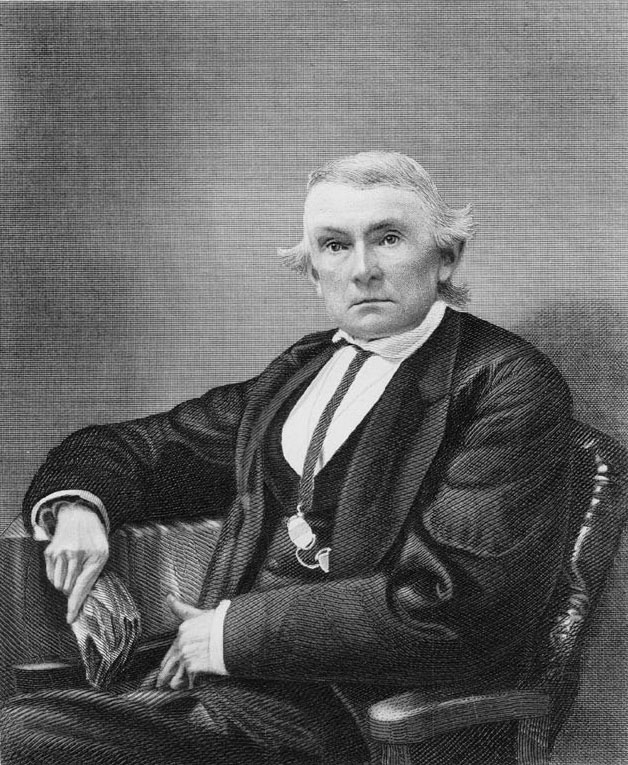

Courtesy of Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Confederate Vice President

Despite grave misgivings, Stephens ultimately signed Georgia’s ordinance of secession. To his consternation, the recently retired congressman was then selected with nine others to represent his home state at the Provisional Confederate Congress in Montgomery, Alabama, in February. There his status as the South’s most outspoken former Unionist won him the vice presidency. By so elevating Stephens, the Montgomery delegates hoped to solidify support for the new nation among cooperationists and other moderate elements.

Courtesy of Civil War Treasures, New York Historical Society

On March 21 Stephens extemporaneously delivered in Savannah what has become known as the “Cornerstone Speech.” In the speech, Stephens explained fundamental differences between the Confederate and U.S. constitutions and the reasons for Southern secession. He declared:

[The Confederacy’s] foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.

Initially, Confederate president Jefferson Davis consulted his vice president frequently, and Stephens appeared to be part of the president’s inner circle. That changed, however, once military concerns began to consume the administration’s attention. “Little Aleck” was no military man, and Davis found little time for him after hostilities began in earnest. Stephens likewise had less and less use for the Richmond, Virginia, government, and the amount of time he spent in the Confederate capital decreased commensurately. He grew disaffected with Davis’s nationalist bent and lent encouragement to Georgia’s governor, Joseph E. Brown, who was a vigorous advocate of states’ rights.

Still, Stephens continued to perform some governmental functions, and in 1863 he attempted to initiate an exchange of prisoners with the North. That effort failed, but the vice president used the correspondence with his Northern counterparts to begin to push for a negotiated end to the war. There was little enthusiasm for such a solution in either the North or the South, but Stephens persisted in his hope that diplomacy could prevail. When a meeting with Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward was arranged at Hampton Roads, Virginia, in February 1865, President Davis—who, significantly, did not attend—sent Stephens to head the Southern delegation. Of course, the North could accept no terms that allowed the Confederacy to continue to exist, and the negotiations came to nothing. In general, then, Stephens’s tenure as the Confederate vice president may be characterized as a rarely broken string of frustrations and disappointments.

Postwar Career

After the war Stephens was imprisoned for five months at Boston’s Fort Warren. Upon his release, Georgia’s citizens elected him in 1866 to the U.S. Senate under President Andrew Johnson’s forgiving Reconstruction scheme. Northerners were naturally dismayed by the prospect of the vice president of the Confederacy sitting in the Senate chambers a year after the Civil War ended, and congressional Republicans refused to seat Stephens. He used the resulting hiatus from public life to pen A Constitutional View of the Late War between the States (1868-70), his two-volume apology for the Confederacy.

Image from Clement Anselm Evans

Although not a member of the Bourbon Triumvirate that ruled over a “redeemed” Georgia, Stephens rose once more to political prominence after Reconstruction. He returned to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1873, and he served there until 1882. That same year he was elected governor of the state but died in office on March 4, 1883. Stephens’s grave is on the front lawn of his Crawfordville home, Liberty Hall, now a state park maintained by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Stephens County in north Georgia is named for him.