Georgia was a leader in the textile industry during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Regional production of silk and cotton provided raw materials needed to produce a wide range of material objects. The construction of textile mills and mill towns in the nineteenth-century led to the development of a distinctive industrial heritage.

The rise of the textile industry in Georgia was a significant historical development with a profound effect on the state’s inhabitants. The narratives surrounding textiles, particularly the cultivation and processing of cotton, form a distinctive industrial heritage that begins with the founding of the Georgia colony in 1732, before cotton dominated the state’s agricultural economy and years before Georgia became the South’s leading producer of textiles.

Silk Production

In the seventeenth century, silk became a fashionable fabric for the European upper classes, and England hoped to compete with the thriving silk industries in France and Italy.

Photograph by Wikimedia

The colonial trustees developed a plan for textile production in the Georgia colony, and in 1734 General James Edward Oglethorpe established the Trustee Garden in Savannah for agricultural experimentation. Among the plants cultivated in the garden were mulberry trees, the leaves of which were used to feed silkworms. Silk production proved difficult for the untrained Georgia colonists, however, so skilled Italian silk makers were brought in to teach them the process. The colonists attained success within the year; records show that Queen Caroline of England wore a gown made of Georgia silk in 1735.

About twenty-five miles northwest of Savannah, the German-speaking Salzburgers of Ebenezer were also attempting to produce silk, and by the late 1730s they had silk operations in place. Seasonal temperature variables, however, were detrimental to the sensitive silkworms and hindered silk production. By the 1780s the hardier and more lucrative cotton crop was being cultivated as a replacement for silk, yet silk production did not die completely in Georgia. As late as the 1830s, some communities, including the town of Canton in Cherokee County, were still attempting to manufacture it. Named for the silk city of the same name in China, Canton was ultimately unsuccessful at establishing a silk center.

The Emergence of Cotton Production

The cotton gin was invented in the 1790s by Eli Whitney at Catharine Greene’s Mulberry Grove plantation in Chatham County. This labor saving tool gradually transformed cotton into a profitable crop, and cotton cultivation increased rapidly across the state during the nineteenth century. White planters, in turn, used enslaved Black workers to plant and harvest acre upon acre of cotton. Industrial-scale cotton production in the state gradually emerged in later decades.

Image from National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

After the War of 1812 (1812-15) some southern leaders, in an attempt to duplicate the prosperity of cotton mills in New England, built textile factories in the South. The earliest of these mills in Georgia were the Antioch Factory in Morgan County and the Bolton Factory in Wilkes County. Both factories, built around 1810, had failed by the early 1820s, largely due to the regions’ rural economy, sparse population, and and underdeveloped transportation network. The idea of textile mills as a means of commerce resurfaced when an economic depression in 1837 required alternate sources of revenue for southern businessmen. Simultaneously, more land was becoming available for cotton cultivation in central and west Georgia after the forcible and violent removal of the Creek Indians.

Early textile manufacturing establishments consisted of small mills, limited in size and scope, that produced coarse fabrics for grain sacks. The locations of these factories were confined to areas in which swiftly moving waterways could be harnessed to power the mill machinery. As a result, the mills were often located along fast moving rivers or the along the fall line, a land area several miles wide that runs along the border between the hilly Piedmont region and the Upper Coastal Plain, from Columbus to Augusta. The fall line marks the prehistoric ocean’s shoreline; land north of it is higher in elevation than the land to the south. As a result, waterways along the fall line pick up speed as they drop to a lower elevation.

Photograph by andrewI04

The topography along the fall line may have been right for mill operations, but the lack of easy access to a white workforce led the first mill operators, also plantation owners, to use enslaved people as textile workers. Other factories employed members of local, white farm families when they were available.

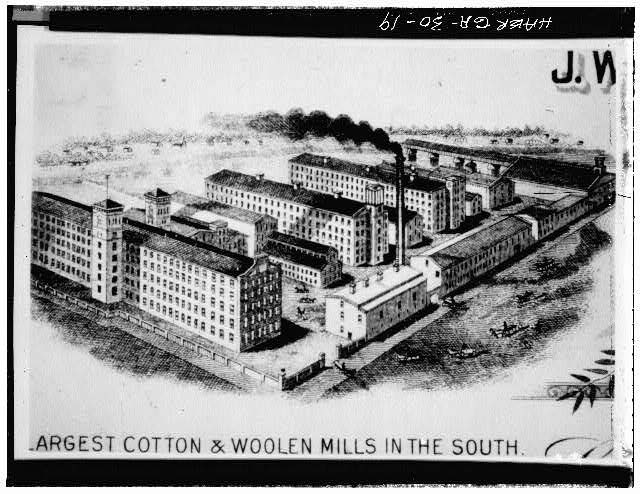

Two prominent Georgians were involved in the state’s first successful mills. In 1829 Augustin Smith Clayton, a well-known lawyer and judge, and his business partners opened the Georgia Factory in Athens, on the banks of the north Oconee River. This mill location also became the site of Whitehall, Georgia’s first mill village, when the property was sold to John White in 1835. Around the same time William Schley, a Georgia governor, constructed the Richmond Factory on Spirit Creek in Augusta in 1834. Encouraged by these profitable enterprises, other businessmen also ventured into the industry. By 1840 nineteen textile mills were in production in Georgia. The mills were becoming larger, too; one of the largest was Roswell Manufacturing of Cobb County, which opened in 1839.

Courtesy of Owens Library, School of Environment and Design, University of Georgia

Sensing the emergence of a profitable enterprise for their state, political leaders passed legislation making it easier for potential mill operators to incorporate their businesses. The industry began to flourish, and by 1850 Georgia had thirty-eight textile mills. The cloth produced in the mills evolved from early coarse fabrics, sometimes called “Georgia wool,” to cotton duck, a heavier canvas-like material. Most of the regional mills in operation at this time were small, with fewer than 2,000 spindles and 100 workers. Often these mills were situated next to the local gristmills, flour mills, and sawmills.

In Georgia’s emerging cities, however, factories tended to be larger. One example was Eagle Manufacturing Company in Columbus, opened in 1851 by William H. Young, a native New Yorker. The growth of the textile industry in Georgia, along with the population increase and expansion of railroads in the state, prompted William “Parson” Brownlow, a Tennessee newspaper editor, to call Georgia “the New England of the South” in 1849.

As the 1850s progressed, Georgia mill owners focused on improving rather than expanding their factories. Employees, by then strictly composed of rural whites from surrounding areas, were developing into a skilled workforce. Some owners in the state encouraged seasoned northern mill workers to relocate to Georgia factories, where they could pass along their experience to local workers; some experienced mill workers came from as far away as England.

Civil War and Its Aftermath

When the Civil War (1861-65) broke out, the mills that remained in business began manufacturing uniforms, blankets, and other supplies for Confederate troops. With much of its manpower depleted by the army, the trained workforce became mostly white women. By 1864 the expertise and loyalty of the mill operatives was perceived as problematic to the Union army. Two of Georgia’s largest factories, New Manchester in Campbell County (later Douglas County) and the Roswell Mill in Cobb County, were among those targeted for destruction by Union general William T. Sherman’s troops during the Atlanta Campaign. To ensure that the workers of these mills did not seek employment elsewhere in the Confederacy, Union forces moved the mostly female workforce of the New Manchester mill to the Roswell Mill, and from there charged the women with treason and deported them north by train. The troops then burned the mills.

Photograph by Evangelio Gonzalez

Not all the mills in Georgia were destroyed by Union troops, however. The Trion Factory in Chattooga County, the first cotton mill built in northwest Georgia, was spared. One of the owners, Andrew Allgood, convinced Union general William T. Sherman that his factory had produced cloth for the Confederacy under protest and that he was, in fact, a “Union man.” As a result Sherman issued protection papers for the mill.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, cotton production in Georgia reemerged as the single most important factor in the state’s economy. As Reconstruction waned in the state, an economic depression in 1873 caused small farmers and businesses to suffer from a lack of capital. The abolishment of slavery and emancipation of Black workers had already caused many plantations to cease operations, and as the southern rail network expanded further, a major transformation began to occur in the state. Georgia’s agricultural financial base shifted toward a new industrial focus, and textile factories became a far more viable means of commerce.

New South Expansion

During the 1870s and 1880s, Henry W. Grady of the Atlanta Constitution encouraged industrialization in the state and implied that civic responsibility required the construction of a cotton mill in every Georgia town. Community leaders, fueled by Grady’s rhetoric and a series of cotton expositions held during the 1880s in Atlanta, took up a new rallying cry: “Bring the cotton mills to the cotton fields.” What followed was a three-decade boom in cotton mill construction; the new drive toward industrialization was coined the “Cotton Mill Campaign of the New South.”

In addition to the construction of new mills, some of the mills damaged or abandoned during wartime were rebuilt. In Columbus, William Young restored his Eagle Factory, renaming it the Eagle and Phenix Mills. The name referred to the mythical phoenix, which, like Young’s factory, had risen from the ashes of war. Lafayette and Ward Lanier, both Confederate veterans, founded West Point Manufacturing in West Point when they purchased the old Chattahoochee Manufacturing Company. Throughout Georgia and the rest of the South, these newly rising mills served as more than just manufacturing establishments; they were symbols of survival and growth for individual communities and the region as a whole.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

After 1880, as many Georgia mills reached profitability, northern business interests began investing in the southern enterprises. Northern investors often preferred to locate their mills in the South, where the taxes were lower, the climate was milder, and the labor was cheaper than in the North. The investors’ added capital allowed a number of mills to expand, and several cities emerged as the state’s major textile production centers. Augusta, Columbus, LaGrange, and Macon all embraced the new industry with rapid growth and positive financial returns.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

By 1900 textile manufacturing was a major industry in Georgia; according to the U.S. Census, that year the state had ninety-eight textile mills in operation. Young men were encouraged to gain skills in the cotton-trade schools that were emerging statewide, and the Textile Department of the Georgia School of Technology (later the Georgia Institute of Technology) opened in 1899. (The department later became known as the School of Textile and Fiber Engineering, and in 2003 the name was changed to the School of Polymer Textile and Fiber Engineering.)

Steam-Power Technology

During the 1830s, the technology for powering mills with steam became available, but the use of steam did not gain popularity in Georgia until the 1850s. Steam power—created by burning wood or coal—freed mills from their reliance on waterpower and allowed owners to situate their enterprises in urban areas other than those along the fall line. In the years after the Civil War, as improvements were made to the steam engine, steam-powered mills became competitive with mills that operated solely by waterpower.

One example of a steam-powered mill was the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills in Atlanta, which originated in 1868 to produce cloth and paper bags. The owner of the mill, Jacob Elsas, had always used steam to operate his factory. As he expanded operations in the 1880s, he installed a huge steam engine that was said to be one of the largest in the South.

While some mill owners began using steam power, others tested a new style of waterwheel, the turbine. Turbines were more efficient and smaller than the older waterwheels; they could process more water by spinning much faster. Some southern mill owners found turbines so effective that they continued to use them into the 1930s.

In Augusta, a canal constructed in 1845 provided an alternate source of power for the mills that were built along its banks. During that time the city was nicknamed the “Lowell of the South,” after the successful industrial town of Lowell, Massachusetts. In 1875 Chinese contract laborers were hired to widen the canal to accommodate more traffic.

Mill Villages

The mill village, part of a family labor arrangement widely used by Georgia mill operators, was adapted from a system developed around 1810 by Samuel Slater, a New England mill owner. In Slater’s system, entire families were employed at the mill and provided with a company-owned house. The northern businessmen who invested in southern mills liked the idea of keeping the families together in order to gain a loyal workforce that would work at the mill for generations. The communities of company-owned homes that grew up around the factories were called mill villages. The owners usually collected rent from the workers; the amount of rent was sometimes determined by how many family members worked in the factory.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

During the 1880s widows with children, assured of decent housing, arrived at the mills in large numbers. Because widespread poverty still existed in Georgia, obtaining a mill job was often the best means of employment. Often mothers would tend the home while the children worked at the factory. In 1890 men accounted for 37 percent of textile mill workers, women 39 percent, and children 24 percent. By 1910 Georgia’s 116 mills employed more than 27,000 people, many living in company housing. According to a 1923 Georgia Railway and Power publication, “There is a spirit about these Georgia mill communities. . . . it constitutes one of the highly valued elements of cotton manufacture in this state.” Two examples of well-known mill villages in Georgia include Cabbagetown, the mill village for Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills, and Whitehall in Athens.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

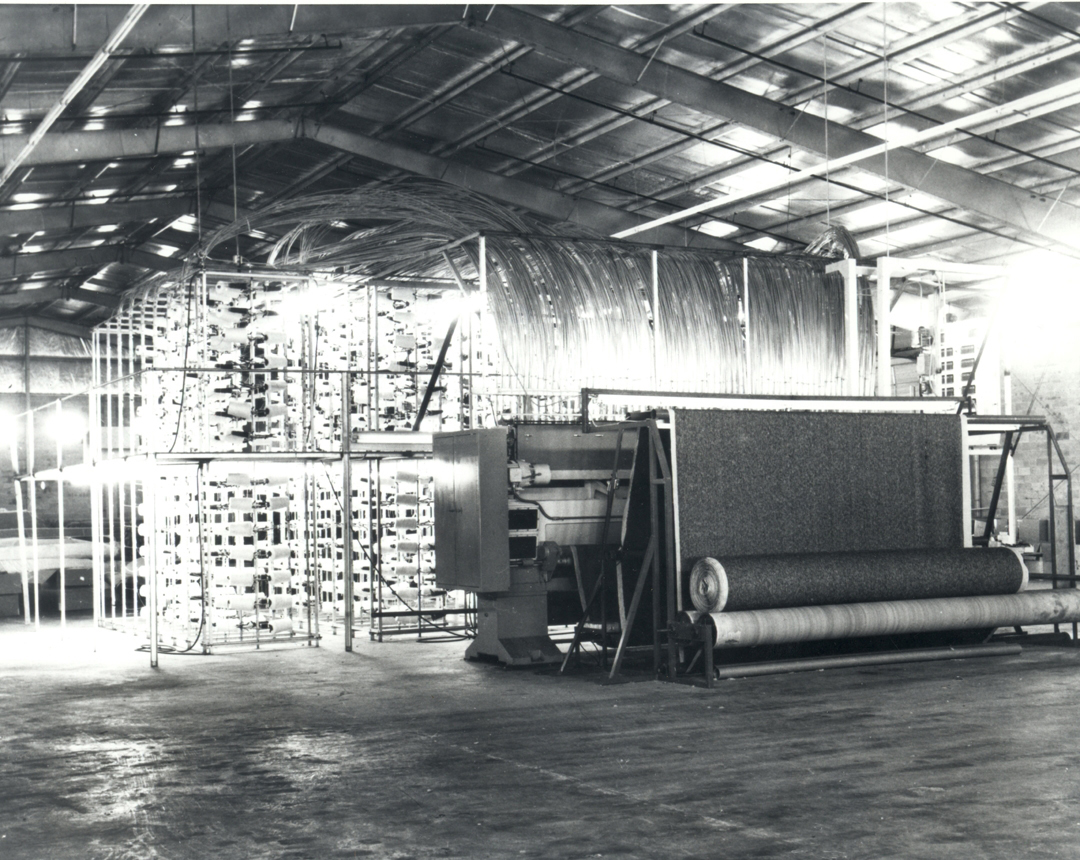

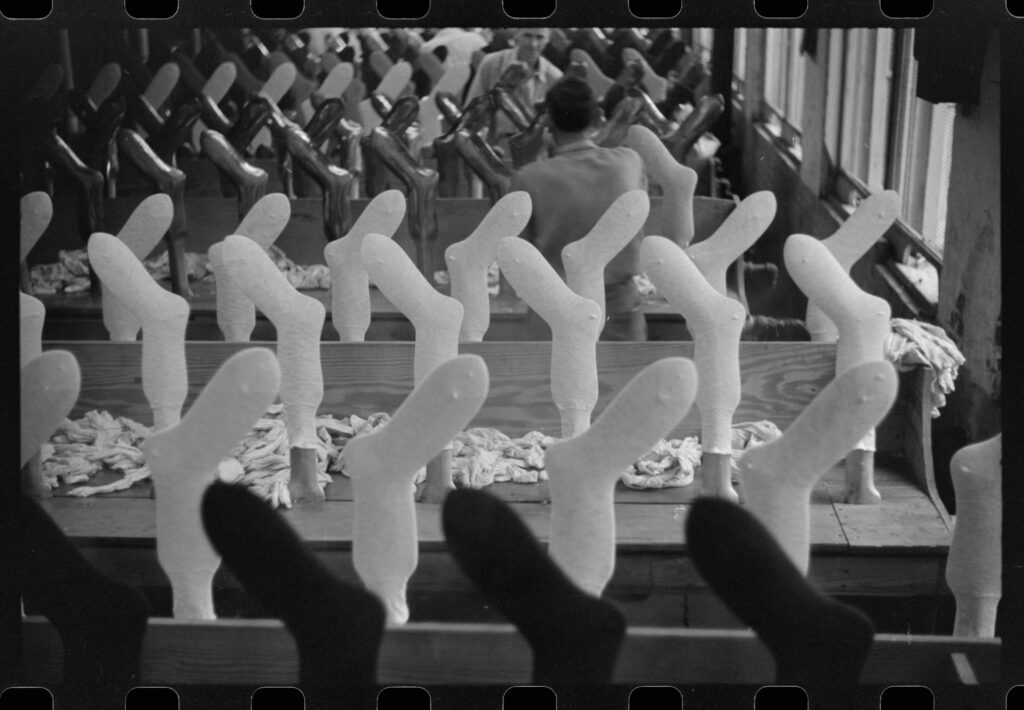

Twentieth-Century Expansion

After 1900 the mill boom continued in Georgia, with companies branching out to other areas and to the production of new types of textiles. By 1908 the Bibb Manufacturing Company of Macon was operating seven mills that produced a variety of cotton products, including hosiery, carpet yarn, twine, spooled cotton, and tire fabric for the budding automobile industry. By 1915 Fuller E. Callaway Sr. owned nine profitable mills operating in or near LaGrange; these too had branched out by manufacturing products for the automobile industry.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

Small mills around the state produced cotton sheeting, shirting fabrics, and different types of twine and rope. They also experimented with textile variations. In the Dalton area Catherine Evans (Whitener) began selling chenille bedspreads in 1900, thereby creating the tufted-textile industry, which later evolved into a worldwide carpet industry.

World War I (1917-18) marked a turning point in the textile industry. The United States’ entrance into the war created a high demand for cloth to outfit American troops, and many Georgia mills were awarded government contracts. As the workload at the factories began to increase, however, male mill operatives were drafted into the armed forces, and some of the mills’ women workers headed home to help on family farms; labor shortages occurred as a result. At Crown Mills in Dalton, managers requested that the government excuse some of their workers from the draft, and mill owners across Georgia, aware of competition among plants, offered higher wages and better homes to attract workers to their factories.

Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

After the war, the industry faced new challenges. Around the state, mill families had suffered the loss of family members, some in wartime, others during the influenza epidemic of 1918. Cotton farmers were devastated by the boll weevil. Even changes in fashion affected production at the factories; new shorter skirt lengths required less fabric and, in turn, fewer workers. Even though new hosiery mills were hiring, the larger factories, faced with wartime surpluses of fabric, had too many employees.

Additional challenges for the workers included the introduction of new machinery that required very few people to operate. Mill owners, in an effort at efficient production, brought in outside consultants to conduct time studies. The result was what mill workers termed the stretch-out. A stretch-out meant that fewer workers were responsible for more machinery and greater production, with little time to accomplish their tasks. The prosperity experienced prior to World War I ended, and workers scrambled to maintain their jobs, often to no avail.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

To individual mills, the popularity of the automobile meant renewed opportunity and competition. Even smaller textile mills signed contracts to manufacture components for automobiles, including tire cord and rubber products. Many mills added rubber manufacturing facilities to their existing factories. These often proved costly to operate, however, and some mills were forced to close or sell off their rubber manufacturing facilities by the 1930s. Such was the case at the Stark Mills of Hogansville in northern Troup County; the factory was sold to U.S. Rubber, a firm that later became Uniroyal.

Racial Segregation

For African Americans, life in the Jim Crow South meant limited job opportunities. The textile industry in Georgia was strictly segregated; Black male workers held only menial jobs at the factories and were not permitted to live within the mill villages. Black women had virtually no role in mill work before the 1950s. They were employed by mill families to cook, clean, and watch the younger children in the mill village.

In an industry that often struggled to remain solvent, white workers viewed the possibility of Black mill employment as a threat to their jobs, and, in turn, intimidated African Americans. During World War I, many industries in the northern states experienced labor shortages, and minority workers were able to get good jobs in that part of the country. Following the war, industrial growth in the North continued, while southern textile mills faltered. The knowledge that a good job could be obtained outside of the region encouraged large numbers of African Americans to leave, in an exodus that became known as the Great Migration.

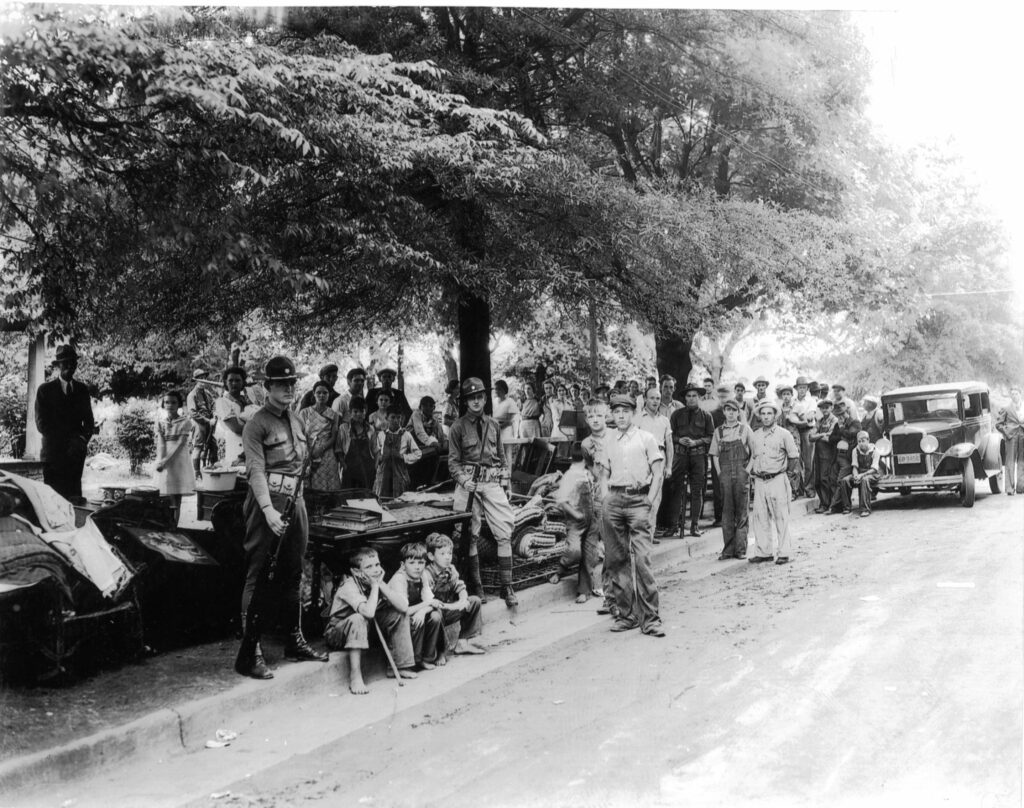

Labor Unrest

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, smaller Georgia mills were forced to shut down, leading to significant unemployment for many mill families. In 1933 passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act, part of U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, required mill operators to follow rules related both to hours in a workday and to employee wages and benefits. Children under the age of sixteen could no longer be employed. When some mill operators chose to ignore the codes, workers protested, believing that the codes offered protection against unfair treatment, as well as the right to unionize.

As mill workers became more confident, incidents of protest over code violations broke out around the state. The protests came to a boiling point when workers called a strike on September 1, 1934. This General Textile Strike of 1934, later termed the Uprising of ’34, involved more than 200,000 northern workers and 170,000 southern workers and was the largest labor protest in the history of the South; approximately 44,000 workers participated in Georgia. Some were drawn out of their factories by “flying squadrons,” or caravans of cars filled with workers who traveled between mills and encouraged others to join the strike.

In some instances, violence broke out between picketers and the guards hired by mill bosses. In Georgia, scattered episodes of violence were recorded at plants in Cedartown, Columbus, Macon, and Porterdale; deaths were reported at Trion and Augusta. These incidents, along with other fatalities in North Carolina and South Carolina, angered workers in Georgia, many of whom joined local branches of the national United Textile Workers (UTW) union. In 1934 there were sixty local branches of the UTW in Georgia.

Courtesy of Troup County Archives

Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge, afraid of massive violence breaking out in the state, declared martial law, and strikers who continued their protests were arrested. The first arrests, many of them women workers, were from the Sargent and East Newnan Cotton Mills in Coweta County. Members of the Georgia National Guard, armed with bayonets, transported the strikers in military trucks to Fort McPherson in Atlanta, where the workers were incarcerated in outdoor holding cells formerly occupied by German prisoners of war during World War I. Those arrested were held there until the strike ended three weeks later, after the UTW received government assurances that the problems at southern textile mills would be investigated.

Courtesy of Special Collections & Archives, Georgia State University Library.

Following the strike, most Georgians believed that the mill owners had prevailed. The strikers were forced to return to unimproved working conditions, and many strikers, especially strike activists, were banned from returning to work in textile factories. Some were also forced out of mill housing with only the clothes on their backs. Workers fearful of being blacklisted turned away from organized labor, and many never discussed the strike again. While the problems at the mills would eventually be addressed, most of these positive changes did not occur until America’s entry into World War II (1941-45).

World War II Years

When the United States entered World War II, wartime contracts brought renewed profitability to mills. Once again they were able to hire more workers. Different fibers, such as nylon, went into production for troop use. The American Chatillon Corporation, an Italian-owned company located in the Rome area, produced synthetic silk for parachutes. The largest war-industry textile producer in the nation was the Bibb Manufacturing Company, which manufactured such items as camouflage nets, life rafts, gas masks, and uniforms.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

Patriotism prevailed among the workers. Many workers actively participated in home-front activities, such as scrap metal drives, and some Georgia textile mills went above and beyond to produce the fabric for military uniforms. When the war ended, some of the mills received the U.S. President’s “E” Award for outstanding service to the war effort.

Modernization, Decline, and Adaptation

After the war, textile mill production continued to prosper for a time, and by the mid-1950s southern mills processed 90 percent of the cotton produced in the United States. But the industry was once again forced to endure changes.

As new technology developed, the mills became increasingly automated. To stay profitable, costs were cut and workforces drastically reduced. The mill operators began selling off the houses in the mill villages as early as the 1940s. The homes were first offered for sale to workers, who were able to purchase them at reasonable prices. By the 1970s all the textile companies had sold their houses; some villages, which had previously been separate entities, became incorporated into nearby cities.

The factories were transformed in other ways as well. With the introduction of new robotic machinery, computers, and high-speed equipment, the workforce was further reduced. In 1971 the U.S. Congress established the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a federal agency charged with enforcing health and safety legislation in all factories. Older mills, many with outdated and hazardous machinery, did not have the capital to invest in new equipment and were forced to close.

In 1994 the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) eliminated quotas between the United States, Canada, and Mexico on fabric products manufactured in those three countries. Some large textile corporations viewed NAFTA as an opportunity to globalize Georgia’s varied textile industry, while others feared job loss and lower wages. NAFTA spurred trade and development in some industries, but textile production continued to decrease in Georgia. Outsourcing work to low-cost Asian textile companies became a more viable financial option for some struggling plants in the 1990s, eventually leading to additional plant closures.

Courtesy of Carpet and Rug Institute

Mill closures affected towns all over the state. At Dawson, in Terrell County, workers at the Almark Mills realized that the company was going bankrupt, obtained loans, and formed the Dawson Workers-Owned Cooperative to buy back the mill. Three years later, in 2001, the group dissolved and the mill closed.

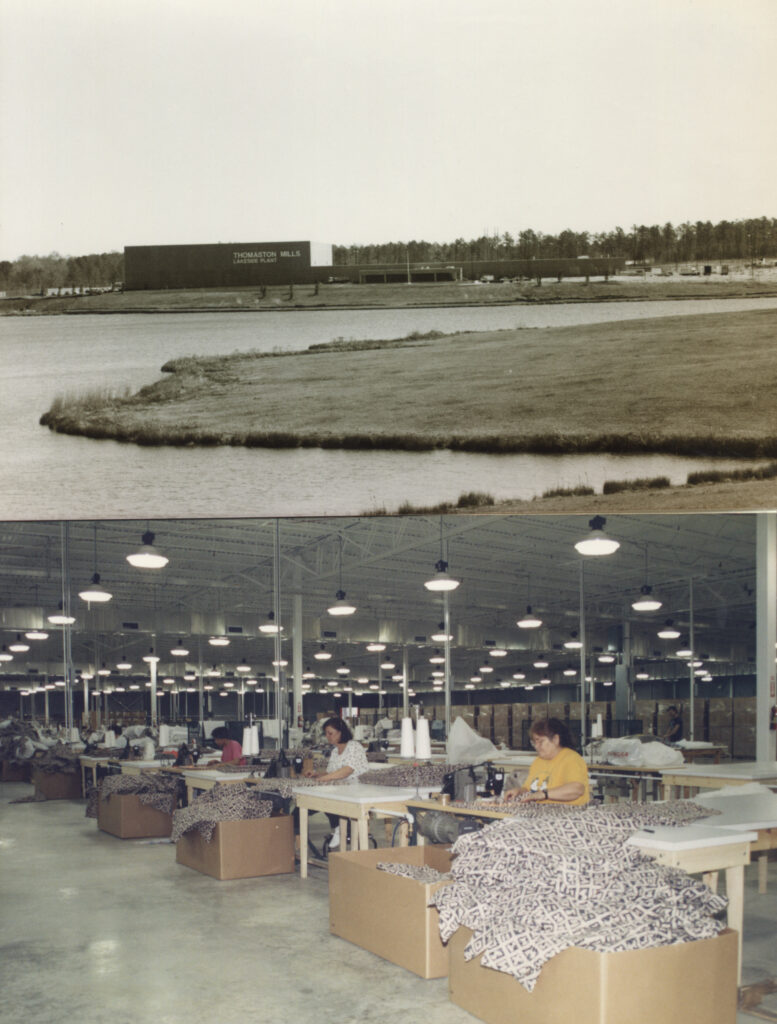

Courtesy of Thomaston-Upson Archives

In 1996 total employment in the U.S. textile industry dropped to 4 percent of all industrial workers nationwide. In Georgia, just 16.5 percent of industrial workers remained in the textile industry–a 50 percent decrease from the 1950s. In the northwest portion of the state, including Bartow, Gordon, Murray, and Whitfield counties, however, unemployment rates remain lower due to the thriving carpet industry. During the 1980s manufacturers in need of more workers began to hire Hispanic immigrants then settling in the Rome area. Some plant managers believe that the industry continues to thrive because of this population’s labor.

Other textile mills in Georgia shuttered their doors during and after the Great Recession. In 2008, Georgia Narrow Fabrics moved production from Jesup to Honduras. In February 2020 Mount Vernon Mills in Alto announced their impending closure and laid off 600 employees. With fewer and fewer mills operating in the region, many of these minimally skilled workers moved into other fields, some finding work at nearby meat processing factories or other manufacturing plants. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 19,300 textile mill jobs remained in Georgia in 2017—a 60.5% decrease since 2001. A few small mills still operate within the state, but cotton is no longer king in Georgia. China is now the largest producer of textiles.

Photograph by Ed Schipul

In an effort to save some of the mill structures from certain demolition, communities around the state began participating in movements to revitalize abandoned mill buildings. In Newnan, the East Newnan Cotton Mill was transformed into rental units and named the “Newnan Lofts.” In Atlanta, the mill housing area of Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills, became the “Fulton Cotton Mill Lofts” in one of the biggest loft conversions in the United States. The former Enterprise Mill in Augusta was redeveloped into loft apartments and office and retail space. Smaller mill sites, situated near picturesque flowing creeks, are now desirable locations to locate guest cottages, executive retreats, and spa complexes. One example is the Historic Banning Mills, an inn located on Snake Creek, an arm of the Chattahoochee River in Carroll County. The inn was built on a 1,300-acre mill site and is located near the original Banning Mill textile building. In other instances, crumbling brick and mortar are all that remain of these once vital sites of production.