The boundary lines that define the state of Georgia are significant for a variety of reasons, such as ownership of physical territory, jurisdiction for the state’s laws, and the state’s rights within the federal system. The determination of Georgia’s boundaries over time has been fraught with conflict, controversy, and uncertainty.

Georgia Territory as Defined in Its Charter

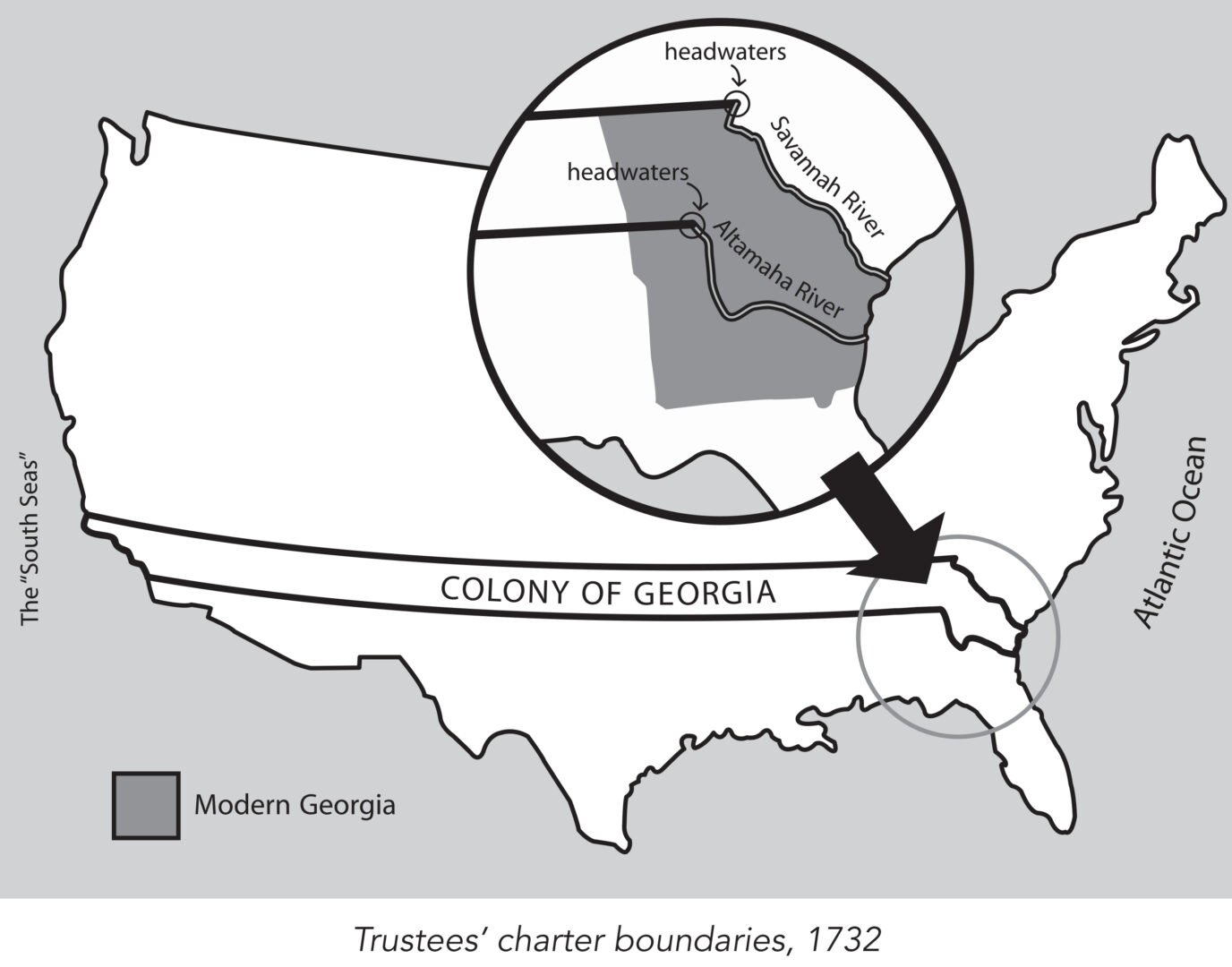

King George II granted James Oglethorpe and the Trustees a charter in 1732 to establish the colony of Georgia. This charter provided, among other things, that the new colony would consist of all the land between the headwaters of the Savannah and the Altamaha rivers, with its eastern boundary formed by the Atlantic Ocean and its western boundary by the “south seas,” a reference to the Pacific Ocean. The latter designation encompassed a tremendous amount of land, most of which was unexplored and unclaimed.

As early as 1683 French explorers claimed land west of the Mississippi River, which they called Louisiana, but the boundaries of this territory were not fully delineated. Over the next several decades, the French were primarily active in Canada, developing a fur trade with the Indians there, and establishing settlements in present-day Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. From the 1730s until 1783, they caused problems for the Georgia colonists by migrating eastward from the Mississippi River to claim additional land and to trade with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek Indians.

By the 1730s the Spanish were organized in Florida and had claimed land as far west as the Mobile River in present-day southwest Alabama and had missions west of the Mississippi River in what is now Texas and New Mexico. They caused a constant military problem for the British colonies by moving north from St. Augustine, Florida, but after Oglethorpe’s victory in 1742 at the Battle of Bloody Marsh, on St. Simons Island, they no longer posed a threat.

The French and Indian War

Georgia’s original boundary remained the same from the founding of the colony until 1763, when the French and Indian War ended in a major territorial victory for the British. England, France, and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris in 1763, and for the first time since Christopher Columbus discovered the New World, England gained complete control of all the land in North America east of the Mississippi River, from Canada to the tip of the Florida peninsula.

Georgia took on a new shape as a result of that treaty, with its western boundary becoming the Mississippi River rather than the Pacific Ocean. The rivers in colonial America were the superhighways of the time, providing routes for commerce and transportation. Having a presence on the Mississippi River opened up the western part of the colony to new settlers, facilitating trading w ith Indian tribes in that region.

In 1763 the British divided what had been Spanish Florida into the two new colonies of West Florida and East Florida, with the Apalachicola River serving as the dividing line between them. West Florida, with Pensacola as its capital, extended west to the Mississippi River. East Florida included all the land east of the Apalachicola River, with St. Augustine as its capital. At the same time, Georgia’s royal governor James Wright received permission from the king of England to expand the boundaries of Georgia to include the territories between the Mississippi and Chattahoochee rivers not granted to the Florida colonies. As a result, Georgia’s southern boundary was extended down to the northern boundary of East Florida.

Aftermath of the Revolutionary War

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Revolutionary War (1775-83), fixed the 31st latitude north as the southern boundary of the new United States. The line extended from the Mississippi River eastward to the Chattahoochee River, moved down that river to its junction with the Flint River, and then followed a direct line east to the headwaters of the St. Marys River. As a result, Georgia’s southern boundary was also that of the United States.

In a separate treaty between England and Spain, England ceded both East and West Florida back to Spain, which now gained control of the lower Mississippi River. This situation created tensions between Spain and the United States for the next dozen years because Spain refused to allow commercial traffic other than its own to descend the river.

After much negotiation, the two countries signed the Pinckney Treaty in 1795, which opened commercial access to the Mississippi River and the port of New Orleans. Equally significant, the treaty designated the boundary between the two countries as the 31st latitude north. Georgia’s boundaries were not affected.

Western Boundary

After the Revolutionary War, the new states began ceding the western portions of their territories to the United States in exchange for the federal government repaying their war debt. In 1802 Georgia became the last state to cede its western lands, compelled to do so in the wake of the Yazoo land fraud, one of the most egregious land scandals in the history of the United States.

The Yazoo land fraud occurred in 1795, when the Georgia General Assembly sold millions of acres along the Yazoo River (in present-day Mississippi) for pennies to Georgia legislators, state officials, and other investors, many of whom resold the land for huge profits. When news of these misdeeds reached the public, the outcry was huge and the sale was overturned, but not before hundreds of people had purchased the disputed land. Swamped with claims, the state decided to give up all its land west of the Chattahoochee River to the federal government. In the 1802 Article of Agreement and Cession, the U.S. government agreed to bear all expenses for settling the claims of those who owned land in the Yazoo River country and to pay Georgia $1.25 million.

Following this agreement, the state’s new western boundary began with the juncture of the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers in southwest Georgia and proceeded north to the great bend of the river (at present-day West Point, Georgia). From there it stretched for 160 miles to the Indian village of Nickajack on the Tennessee River and continued from there up to the 35th latitude north. (Nickajack no longer exists; the Tennessee River was dammed in 1913, creating a lake that covers the abandoned site.)

Southern Boundary

Although numerous descriptions of Georgia’s changing boundaries had been written since the colony’s founding in 1732, almost seventy years passed before any of the lines were actually surveyed. With the signing in 1795 of the Pinckney Treaty, in which Spain and the United States agreed on their common border, President George Washington asked surveyor Andrew Ellicott to travel to Natchez, on the Mississippi River, and meet with a Spanish team to survey the boundary line. This line extended from the Mississippi River eastward to the Chattahoochee River, moved down that river to its junction with the Flint River, and then followed a direct line east to the headwaters of the St. Marys River.

Ellicott’s Mound

Ellicott and a fifty-member surveying team arrived in Natchez in February 1797 and spent a year trying to get the Spanish to begin the survey. Finally, in May 1798, the U.S. and Spanish surveying teams met at the 31st latitude at the Mississippi River and began their work. By mid-September 1799 the teams had surveyed 381 miles of the line and were at the Chattahoochee River. Remaining to be surveyed was the portion of the line from the junction of the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers to the headwaters of the St. Marys River.

Because of problems with the Seminole Indians, who were unhappy with the United States and Spain marking a boundary line through their territory, the survey of the next 155 miles was abandoned. The teams split into two, with half walking from the mouth of the Flint River to the village of St. Marys, while Ellicott and twenty others took the equipment and all of his surveying paperwork on a forty-ton schooner and sailed around Florida. Both teams safely met at St. Marys in early December 1799.

The group decided to mark only the headwaters of the St. Marys River without doing any other surveying. Using canoes, Ellicott and members of the team went up the St. Marys into the Okefenokee Swamp. With no distinct spring as the exact source of the St. Marys, Ellicott made an educated decision about the headwaters’ location and marked it with a large mound of dirt. This location is known as Ellicott’s Mound and is marked today by a U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey disc. Both Ellicott’s location of the headwaters and the unsurveyed Georgia/Florida boundary were the topics of numerous disputes and lawsuits for the next sixty years.

The Orr-Whitner Line

In 1819 the United States agreed to purchase West and East Florida from Spain, which was struggling at that time to hold onto its possessions in North America. Established as the Florida Territory in 1822, Florida eventually became a state in 1845. In the decades after the purchase of the territory, at least six attempts were made to prove or disprove Ellicott’s Mound as the legitimate origin of the St. Marys River, and numerous aborted attempts were made to survey Georgia’s southern border.

Finally, in 1859, Georgia and Florida appointed surveyors Gustavus J. Orr and B. F. Whitner, respectively, to complete the survey. The Orr-Whitner line was accepted by Florida in 1861 and Georgia in 1866 as their official boundary, although the outbreak of the Civil War (1861-65) delayed the line’s approval by the U.S. Congress until 1872. The long debate with Florida over Georgia’s southern boundary was finally settled and has not been disputed since.

Northeastern Boundary

Georgia’s charter of 1732 describes the colony’s northern boundary as beginning at the headwaters of the Savannah River. However, it would be more than fifty years, at the Beaufort Convention of 1787, before Georgia and South Carolina further defined the boundary as “the most northern branch or stream of the River Savannah from the Sea or Mouth of such stream to the fork or confluence of the Rivers now called Tugoloo and Keowee, and from thence the most northern branch or stream of the said River Tugaloo, till it intersects the northern boundary line of South Carolina.” (The northern boundary line of South Carolina was the 35th latitude north.) Another twenty-five years passed before a reliable survey determined that the most northern branch of the Tugaloo was the Chattooga River. In the meantime, Georgia’s boundary with South Carolina remained poorly defined, as did its boundary with North Carolina.

As settlers established communities in the western portions of North Carolina, many were unsure in which state they resided. The confusion arose because the 35th latitude north, which was the southern boundary of North Carolina, and thus the northern boundary of Georgia, had never been surveyed. From 1787 to 1811 the citizens of what is now Transylvania County in western North Carolina assumed that they lived in Georgia and elected representatives to the Georgia state legislature.

Ellicott’s Survey

In 1811, to settle the issue, Georgia again hired Ellicott, this time to survey and mark the location of the 35th latitude north. Ellicott’s positive location of the latitude line established that those citizens who thought they lived in Georgia were really in North Carolina. Although Ellicott’s finding resulted in a significant loss of land for Georgia, his survey was accepted by the state and has never been challenged in the courts. For nearly two centuries, records of Ellicott’s survey were believed to be lost.

In 1813 North Carolina and South Carolina each sent a survey team to mark the 35th latitude north at the Chattooga River. The surveyors from both states agreed on its location and carved the inscription “Lat 35 AD 1813 NC+SC” on a huge boulder on the east bank of the river. This rock, known as “Commissioner’s Rock,” is located in the Ellicott Rock Wilderness and is easily reached by hikers. The rock is on the National Register of Historic Places (where it is listed as “Ellicott Rock”) and also marks the point at which the boundaries of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia converge.

Confusion over Ellicott’s Rock

For more than fifty years, hikers, historians, writers, and officials have taken the three-mile walk from the trailhead at Burrell’s Ford campground up the east side of the Chattooga River to visit what is known as Ellicott’s Rock. This small rock is located fifteen feet north of Commissioner’s Rock and has the letters N and either G or C carved on it.

Numerous authors have written about Ellicott’s Rock in surveying, history, travel, and hiking magazines, and most repeat the story line that Ellicott carved those letters in 1811, when he surveyed the 35th latitude for Georgia. The writers also attempted to solve the mystery of Ellicott’s lost records by speculating that because Ellicott found the 35th latitude to be some ten miles south than previously thought, causing Georgia to lose thousands of acres to North Carolina, that Georgia refused to pay him for the survey. The theory continues that Ellicott, in a fit of pique, destroyed all his field notes and his diary of the survey.

Twenty-first-century research conducted in the North Carolina and Georgia state archives tells a very different story. Letters and receipts reveal that Georgia paid Ellicott $4,450 for his survey. Also discovered were his diary, found in an unfinished manuscript, and a draft report of his surveying calculations locating the 35th latitude, intended for Georgia governor David B. Mitchell. Further, the resolution appointing Ellicott to find and mark the 35th latitude north does not mention the Chattooga River, and an 1812 letter from Ellicott to North Carolina governor William Hawkins states: “In the parallel of 35 degree N. latitude, on the west side of the Chatoga river, a stone is set up marked on the South side (G. lat 35 N.) and on the north side, (N.C.) for North Carolina” [emphasis added]. This evidence indicates that the rock on the east side of the river, near Commissioner’s Rock, was not inscribed by Ellicott. A rock matching Ellicott’s description has not been found.

Continuing Disputes

There have been several modifications of the boundary line between Georgia and South Carolina over the years because of alterations along the Savannah River, including erosion, the accretion of islands and banks, and changes in the river course itself. In 1990 the U.S. Supreme Court heard the most recent lawsuit between Georgia and South Carolina, which concerned ownership of some islands in the river and commercial fishing rights.

Northern Boundary

Of all Georgia’s boundaries, the northern boundary with Tennessee has caused the most problems. Tennessee became the sixteenth state in 1796, and its southern boundary was the 35th latitude north. It was not until 1817, however, when the Alabama Territory was separated from the Mississippi Territory, that Tennessee and Georgia legislators passed a resolution agreeing to mark their common boundary.

Georgia’s northwestern boundary was described as a line from the great bend of the Chattahoochee River and “thence, in a direct line, to Nickajack, on the Tennessee river . . . running up the said Tennessee river, and along the western bank thereof, to the southern boundary line of the state of Tennessee.” Three-man surveying teams from both states met at Nickajack to find the 35th latitude north and “plainly mark and designate the same.”

The field notes available from the survey indicate that Georgia team member James Camak, a mathematician, determined where the lines were to be surveyed. Using his knowledge of mathematics and astronomy, Camak calculated in 1818 that the 35th latitude was not north of Nickajack and on the west bank of the Tennessee River but almost a mile south of Nickajack. His calculations were incorrect; according to modern measurements, the 35th latitude is one mile north of Nickajack and in the middle of the Tennessee River. Nevertheless, Camak and both teams marked the line as south of Nickajack and then proceeded to mark it to the east for 110 miles. The teams marked the end of the line and returned to Georgia to file their reports.

In 1819 Tennessee issued a statute defining its boundary with Georgia as “the thirty-fifth degree of north latitude, as found by James Camak,” a statement that haunts Georgia to this day. Georgia’s legislature passed a resolution in that same year authorizing the governor to have the maps of the surveyed lines recorded in the U.S. Surveyor General’s office, but there is no record of any federal law or act certifying or approving the survey as the official boundary between the two states.

Georgia then asked Camak in 1819 to take a team to Ellicott’s Rock and mark a line west from there to connect with the line from Nickajack. The team members proceeded westward, and when they came to where they had stopped measuring the year before, they noted that they were located “661 yards” north of the earlier mark. Instead of remeasuring all their surveys, they simply connected the westward and eastward lines and marked the junction. This offset is still there today and is labeled on all maps as “Montgomery’s Corner,” located in Towns County, just east of Blairsville. Even this portion of Camak’s survey was never on the 35th latitude north.

Alabama was admitted as a state in 1819. Seven years later, in 1826, the governors of Georgia and Alabama agreed to survey the western boundary connecting Nickajack and Miller’s Bend (now West Point), a town on the Chattahoochee River in west central Georgia. Alabama sent commissioners to oversee the work, believing that it was Georgia’s responsibility to mark the line. Georgia again called on Camak as its mathematician. Approaching the mark that he had made eight years earlier, Camak noted that Nickajack was “about one quarter of a mile north of the Georgia/Tennessee boundary as surveyed in 1818.” Modern measurements, however, indicate that Camak’s surveyed line is almost a mile south of the 35th latitude north.

Challenges to Georgia’s Northern Boundary

Georgia’s legislature has voted to revisit its northern boundary line with Tennessee and North Carolina a dozen times over the past 200 years without receiving any response from Tennessee or North Carolina. Confusion over property lines on the boundary has resulted in lawsuits between property owners, but there has never been a lawsuit between Georgia and Tennessee or between Georgia and North Carolina.

The drought of 2008 in Georgia brought renewed attention to the fact that if the Georgia/Tennessee boundary had been properly surveyed along the 35th latitude, then plenty of water from the Tennessee River would be available for Georgia’s citizens. That year Georgia’s legislature passed another resolution, signed into law by Governor Sonny Perdue, strongly urging him to initiate negotiations with the governors of Tennessee and North Carolina to correct Camak’s flawed survey. The legislature also authorized the state’s attorney general to take “legal action to correct Georgia’s northern border at the 35th parallel,” should such negotiations fail to correct the situation. Nothing further occurred as a result of this resolution.

In 2013 Georgia’s legislature passed another resolution proposing a settlement of the northern boundary issue, which became effective without approval of the governor. This resolution provides that “if an agreement resolving the boundary dispute is not reached as of the last day on which the General Assembly convenes in regular session in 2014, the Attorney General of Georgia is hereby authorized and directed to take such action as is required to initiate suit in the United States Supreme Court against the State of Tennessee for final settlement of the boundary issue.”