Wrestling Temptation: The Quest to Control Alcohol in Georgia

From moonshine stills to craft breweries, Georgia has a complicated past with spirituous drink. Discover how a state divided on the issue of alcohol struggled to control its commerce and consumption.

Introduction

Wrestling Temptation: The Quest to Control Alcohol in Georgia traces the struggle to regulate the production, distribution, and consumption of alcohol in the state from 1733 to the early twenty-first century. The exhibit was developed in 2017 by the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies at the University of Georgia to explore how issues of morality, economy, and personal liberty interconnect with the use and abuse of alcohol.

Colonial Georgia

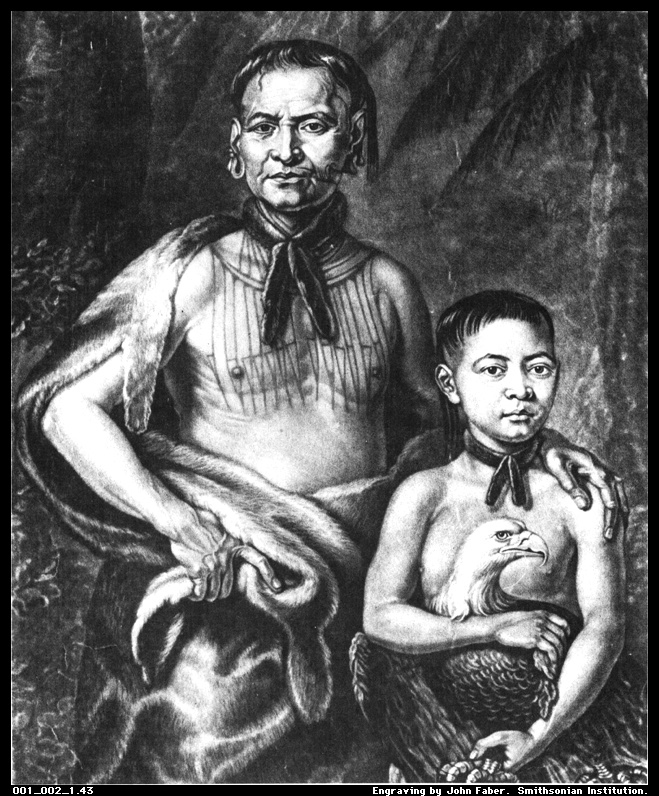

Alcohol has been a part of daily life in Georgia since the establishment of Savannah in 1733. At that time, conventional wisdom held that spirits could cure a variety of sicknesses; they also provided a potable alternative to the local water supply. With few opportunities for leisure, drinking became a favorite pastime throughout the colonies, and the potency and ready availability of liquor made it the drink of choice for many inhabitants. Drinking became so popular, in fact, that Georgia’s colonists became unruly and mutinous under the influence of so much strong drink. The Yamacraw leader Tomochichi noticed an increase in alcohol abuse among the native population as well, and in 1734, he asked James Oglethorpe and the Trustees to forbid the sale of rum.

The Trustees responded the following year by issuing a decree against strong liquors, naming an enforcement officer, and adopting a series of graduated penalties for violators. Additionally, taverns were made to obtain licenses to dispense “light liquor” (beer and wine).

Accusations of corruption in this new system surfaced quickly, and angry colonists protested the restrictions. A faction known as the Malcontents argued that new measures hurt trade as well; losing rum as a means of barter for timber and other exports to the British West Indies led to a significant decline in trade and the colony’s profitability. On September 29, 1742, the Trustees overturned the act and once again allowed the importation of rum for use in the lumber trade.

WCTU and the Fight to Protect Families

Founded in 1874, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was one of the first national organizations devoted to ameliorating social ills. While organized temperance groups began meeting in Georgia in the late 1820s, it was not until the formation of the state’s first WCTU chapter in 1880 that temperance advocates began to attract broad support for their reforms. The state’s first chapter formed at the Trinity Methodist Church in Atlanta, and in the years that followed, local unions organized rallies throughout Georgia and circulated petitions calling for restrictions on the sale and consumption of alcohol. To raise money for their reform initiatives, temperance organizations made quilts to raffle or auction.

Due largely to the efforts of the WCTU and prominent female reformers such as Rebecca Latimer Felton, the Georgia General Assembly passed a local option bill in 1885, granting counties the right to vote on the issue. With this victory in hand, the WCTU set its sights on an education law that would amend textbooks to stress the importance of temperance and warn of the adverse effects of alcohol and narcotics. In 1901 the state legislature passed a hygiene law mandating compulsory temperance education in public schools. By 1907, when the legislature enacted statewide prohibition, most counties had already voted themselves dry.

The Illicit Liquor Trade

Moonshine was a part of life in southern Appalachia long before prohibition. The mountains of north Georgia provided both a steady stream of water to power stills and seclusion from the prying eyes of law enforcement. The product itself offered farmers a source of supplemental income, one which proved easier to transport across mountainous terrain than the corn crop.

During the 1870s the Internal Revenue Service attempted to collect taxes on so-called luxury items such as liquor and tobacco. Not only could many southerners not afford the tax, but they also saw it as an infringement of their liberties and refused to pay. In 1876 the Commissioner of Internal Revenue reported that the federal government lost millions of dollars in annual revenue because southern Appalachian home brewers, including those in north Georgia, avoided paying federal taxes on their products. To recoup lost revenue, federal agents targeted Appalachian communities for increased surveillance, often working with U.S. troops to eliminate illegal distilleries. The resulting “moonshine war” was waged throughout the mountain South, but was particularly deadly in Georgia, which suffered more casualties than any other state targeted in the raids.

When the Georgia legislature passed statewide prohibition in 1907, the moonshine industry expanded to meet demand. In 1914 the Atlanta federal court saw 564 criminal “illicit distillery” cases. Dawson County even became known as the “moonshine capital of America,” a distinction that was applied at one time or another to three other counties in the Southeast. Between the 1930s and 1950s, the peak era of production, federal agents seized more than 500,000 gallons a year with profits in the millions, making moonshining one of the most successful commercial enterprises in the area.

Alcohol as Medicine in the Prohibition Era

In 1917 the American Medical Association (AMA) concluded that alcohol was without therapeutic value of any kind. However, after the passage of prohibition, the AMA reversed its position and identified twenty-seven ailments—including diabetes and cancer—that could be treated with alcohol. In Georgia, Representative Seaborn Wright of Floyd County proposed an amendment to allow druggists to sell alcohol to hospitals and charitable institutions for medicinal purposes.

Many companies looking to turn a profit created alcoholic miracle cures that had to be approved by both the Department of Justice and the Prohibition Bureau in Washington, D.C. In exchange for a small fee, physicians typically prescribed the maximum amount permitted—one pint every ten days. The government allowed physicians to issue one hundred alcohol prescriptions every ninety days, but corruption was rampant, and many exceeded the monthly limit. From 1921 to 1930, doctors earned an estimated $40 million from writing whiskey prescriptions.

Prohibition in Georgia: Neither the Spirit nor the Letter of the Law

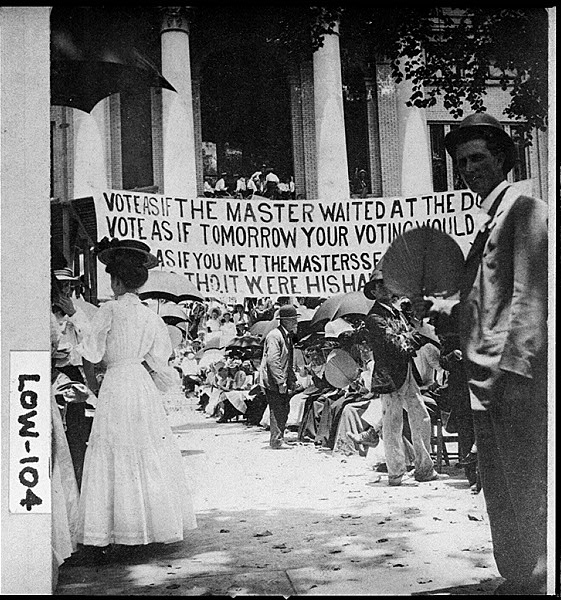

Prohibitionist forces capitalized on the notoriety of the 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, blaming liquor for the violence and using the episode as leverage in the fight for statewide prohibition. Many white southerners saw prohibition as a solution to the region’s “Negro Problem.” When coupled with the gubernatorial victory of prohibitionist candidate Hoke Smith, the riot emboldened legislators to propose a bill banning the sale of spirits statewide. After lengthy debate, the bill passed, and Governor Smith signed the legislation outlawing the sale or manufacture of alcohol in public or at any place of business. The Atlanta Constitution reported that church bells rang out, and supportive crowds took to the streets, rejoicing in song. Georgia was the first southern state to go dry. By 1915, seven other states in the region had enacted statewide prohibition.

Legislative passage of prohibition was a triumph for temperance forces in Georgia, but the bill proved to be riddled with loopholes. Private locker clubs escaped closure by serving alcohol only to their members, while saloons offered near-beer to the less affluent. Upset by legal sidestepping, prohibitionists pressured Governor John Slaton into calling a special legislative session in 1915 to eliminate the locker-club provision, to prohibit mail-order advertisements for alcohol, and to bar the importation of liquor via the so-called jug train.

After the repeal of national prohibition in 1933, various groups in the state organized and lobbied for statewide repeal, hoping to generate much-needed tax revenue. Some argued for responsible regulation and taxation of alcohol as a means of raising funds to aid Georgia’s struggling schools. Nevertheless, staunch dry forces insisted that statewide prohibition be upheld in the name of morality. Facing an economic crisis, Governor Eugene Talmadge reluctantly signed the Alcoholic Beverage Control Act on March 22, 1935, calling for a statewide referendum on the issue of repeal. A vote was held that May granting the State Revenue Commission the right to establish new regulations regarding the manufacture and sale of alcohol. In 1938 Governor E. D. Rivers signed the Revenue Tax Act to Legalize and Control Alcoholic Beverages and Liquors, nullifying all remaining statewide prohibition statutes.

Changing Attitudes towards Alcohol and Alcoholism

For decades, alcoholism was regarded as a moral failing or a sign of personal weakness. This view only began to change in the mid-1930s with the founding of organizations such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which fought to change public attitudes and government policies toward alcoholism. In 1951 the Georgia General Assembly recognized alcoholism as an illness and created a commission to study the problem and find more effective approaches to treating the disease. In the decade that followed, Georgia increased funding to support alcohol rehabilitation services from $17,787 in 1952 to $291,000 in 1962—a 1,536 percent increase.

In 1966 President Lyndon B. Johnson created the National Center for Prevention and Control of Alcoholism within the National Institute of Mental Health. In the years since its establishment, this agency has expanded the scope of research and support for treating and understanding alcoholism as a disease. Nevertheless, millions of Americans still suffer from Alcohol Use Disorder, according to the NIAAA, and alcohol abuse carries steep economic costs for the criminal justice and healthcare systems. The social and emotional costs to those who struggle with the disease are immeasurable

Reshaping Modern Alcohol Policy

Since the 1980s there has been a nationwide uptick in small independent breweries. Tapping into the growth of artisanal food culture in the U. S., these breweries emphasize small-scale production and local ingredients to produce varieties of beer aimed at an upscale market. In 2012 craft beer accounted for only 6.5 percent of sales by volume, but by 2014, its share had increased to 11 percent of U.S. sales by volume with 135 regional craft breweries.

Georgia’s craft brewers argue that regulations adopted in the wake of prohibition are now limiting their expansion. They won a significant victory in 2017 when legislators passed SB 85, which allows craft breweries to sell limited quantities of beer directly to customers. According to the Brewer’s Association, Georgia boasted more than one hundred craft breweries by 2019, with a total economic impact of over $2 billion.