Georgia was home to a number of Confederate prisons during the Civil War (1861-65). Though dwarfed by the shadow of notorious Andersonville Prison, there were fifteen other facilities in the state.

These ranged from well-constructed fortifications, such as county jails, to makeshift installations, such as wooded areas patrolled by armed guards surrounding prisoners. Prison sites were usually selected for their proximity to major transportation routes. Georgia was relatively distant from the battle lines for most of the war, which made it prime ground for incarcerating captured Union soldiers. Conditions at these prisons usually depended on the Confederacy’s military fortunes. Toward the end of the war, as the tide turned against the Confederate army at the battlefront, the government’s ability to supply and provision prisons in Georgia weakened. Conditions deteriorated to the point where prisoners were attempting to survive without the food, clothing, and shelter needed for sustenance.

Prison Sites

One of the first prisons to hold Union soldiers in Georgia was the Fulton County Jail in Atlanta. This facility, built before the war, was large enough to serve as a holding area for more than 150 prisoners in early 1862. The prisoners had been sent to Atlanta to relieve overcrowding at sites in Richmond, Virginia—the same reason such larger prisons as Andersonville later came into existence. On several occasions throughout the war, makeshift facilities were used in and around Atlanta before prisoners were transferred to other sites farther south. This was especially true as large campaigns in both Virginia and Georgia in 1864 swelled the numbers captured.

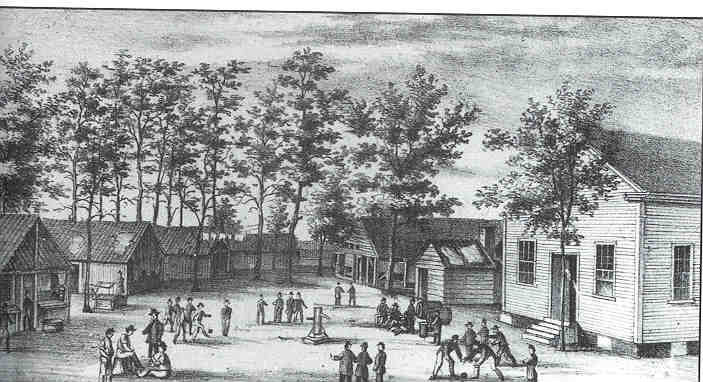

Also in 1862, a prison pen, known as Camp Oglethorpe, was opened in Macon. Wedged between railroad tracks and the Ocmulgee River, the site was enclosed by a rough stockade on fifteen to twenty acres. Nearly 1,000 prisoners arrived in May to find several buildings within, including one large enough to use as a hospital. The prisoners were a mixture of officers and enlisted men. Their living quarters consisted of sheds or stalls already on site or shelters constructed from materials found within the stockade. As a result of a formal exchange cartel agreed on by the combating powers, most of these prisoners gained their freedom, and by the beginning of 1863, Camp Oglethorpe was nearly abandoned.

The breakdown of prisoner exchanges, combined with Union general William T. Sherman’s Georgia campaign, forced the Confederacy to reopen the facility as an officers’ prison. By the summer of 1864, more than 2,300 Union officers were housed there. Shelter was barely adequate, and rations consisted of beans, cornmeal, and rice in meager amounts. The lack of sanitation, coupled with a dwindling diet, led to the usual litany of such diseases as chronic dysentery and scurvy. An official death total for the prison is unknown. Most of the prisoners were moved from the Macon facility by late July 1864 because of Union cavalry raids in the general vicinity, although some officers were held there until September.

The Shadow of Andersonville

When Sherman’s Union army took Atlanta on September 2, 1864, Confederate prison authorities knew that Andersonville would be a prime target of any Union thrust into the heartland of Georgia, and they began moving Union prisoners of war to more secure locations. At Camp Davidson, constructed in July 1864 on the grounds of what had been the U.S. Marine Hospital in Savannah, prisoners were confined within a stockade that enclosed part of an orchard. The ample rations were a welcome respite from the horrors of Macon and Andersonville. The camp guards, the First Georgia Volunteers, had once been prisoners of war themselves. Because of overcrowding caused by the influx of Andersonville prisoners in September, a second Savannah prison, for officers, was set up on land adjacent to the city jail. Another stockade was hastily constructed for enlisted men. This structure, along with Camp Davidson, may have held more than 10,000 men, but both had to be abandoned after only a month and a half of use.

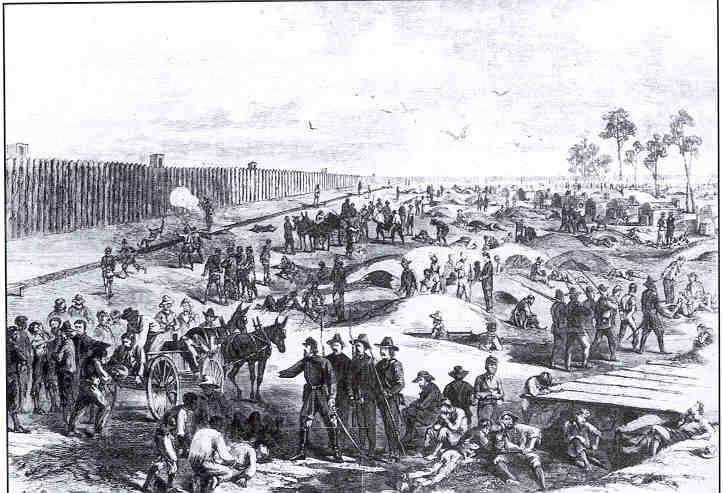

The most substantial prison holding former Andersonville captives was Camp Lawton in Millen, located in Jenkins County between Augusta and Savannah. Camp Lawton was a stockade structure enclosing forty-two acres, making it the largest Civil War prison in terms of area. Set only a mile off the Augusta Railroad, the pen was designed to hold up to 40,000 prisoners, although the population never grew to much beyond 10,000. By all accounts the prison at Millen was infinitely better than Andersonville. A generous spring ran north to south through the site, providing a fresh supply of drinking water. Rations were also more plentiful, since the countryside had yet to be scavenged of its food resources. Yet disease and death were not unknown because many of the prisoners were terribly debilitated from their incarceration at Andersonville. During the short time the prison was open, from late September to early November 1864, nearly 500 prisoners succumbed to disease.

As Sherman’s troops approached Millen in the March to the Sea, the prisoners had to be moved yet again. Many of them were sent to South Carolina, and others were sent to Savannah. The exact site of Camp Lawton was not located until 2010, when its discovery by archaeology students at Georgia Southern University made national news. The find was significant because the site, previously unidentified and thus unplundered, yielded an unusually rich cache of artifacts left by prisoners and their guards. Researchers believe that many of the artifacts are possessions dropped by prisoners as they were forced onto trains during the camp’s final evacuation.

From Savannah approximately 5,000 prisoners were transported down the Atlantic and Gulf Coast Railroad to Blackshear. This camp was basically a makeshift guard line with accompanying artillery pieces surrounding several thousand men in the piney woods of southeast Georgia. As might be expected, escapes were frequent, discipline lax, and resources scarce. The Blackshear area held prisoners for less than a month, from late November to early December. The collapse of the Confederate infrastructure caused much confusion about what exactly to do with these prisoners. Some were shipped back to South Carolina, but the majority went southwest to Thomasville, where the Atlantic and Gulf rail line ended. Impressed enslaved laborers from nearby plantations constructed yet another stockade.

The prison at Thomasville was located half a mile northwest of town, on a five-acre tract surrounded by a ditch six feet deep and ten feet wide. Planned as a temporary holding area, the site was occupied for only two weeks in December 1864. During that time approximately 5,000 Union prisoners were confined there. The men were allowed to construct their own shelters from existing timber within the site. Exposure to the elements and close quarters caused an outbreak of smallpox, which claimed the lives of hundreds of prisoners. Confederate authorities soon ordered the site to be abandoned, and the decision was made to send all of Thomasville’s prisoners back to Andersonville. This meant a sixty-mile march north to Albany, where they reembarked on the Southwestern Railroad. This line took them back to Andersonville, where they arrived on Christmas Eve 1864.

Forgotten History

Though at present Andersonville is a National Historic Site, little has been done to commemorate other Civil War prison sites in Georgia. State historic markers have been erected at Blackshear and Thomasville. Magnolia Springs State Park now incorporates the area of Camp Lawton, including some historic earthworks. Other prison sites, such as those in Atlanta and Savannah, have been destroyed by development.